CLINIC DAY 1:

I woke up at 4 a.m. with something akin to a minor anxiety attack. I’m not usually an anxiety attack prone person, though I admit to having spent many an Hour of the Wolf worrying over things I have no control over. This one was no different. Instead of worrying about my first clinic, though, I was worried about my stupid cat back home in West Virginia. I could just imagine her curled up on the edge of the bed meowing pittifully to herself because we hadn’t come home. And she would have nearly two more weeks of that before we came back. I know it sounds sort of dumb in retrospect, but that’s how my head works. After lying there for nearly an hour fighting to get to sleep and failing because I kept hearing mewing in my head, I took a moment and prayed for the little beast. I prayed her time alone would not be painful and that God would lessen her anxieties as well as mine. After that, I went to sleep.

I woke up at 4 a.m. with something akin to a minor anxiety attack. I’m not usually an anxiety attack prone person, though I admit to having spent many an Hour of the Wolf worrying over things I have no control over. This one was no different. Instead of worrying about my first clinic, though, I was worried about my stupid cat back home in West Virginia. I could just imagine her curled up on the edge of the bed meowing pittifully to herself because we hadn’t come home. And she would have nearly two more weeks of that before we came back. I know it sounds sort of dumb in retrospect, but that’s how my head works. After lying there for nearly an hour fighting to get to sleep and failing because I kept hearing mewing in my head, I took a moment and prayed for the little beast. I prayed her time alone would not be painful and that God would lessen her anxieties as well as mine. After that, I went to sleep.

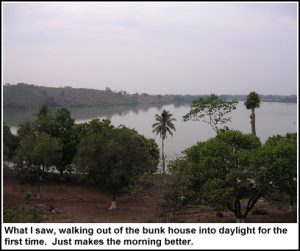

At 5:30, I woke up again and stayed woke up. I wanted to sleep longer, as I actually had until 6:30 before breakfast was served, but I also wanted to get up and grab any available water the showers might have. Sure enough, there was some. Evidently the water pump had found some life during the night and was able to send some water up to the hillside tanks above us. I used it to its fullest. It was so nice to be clean.

At 5:30, I woke up again and stayed woke up. I wanted to sleep longer, as I actually had until 6:30 before breakfast was served, but I also wanted to get up and grab any available water the showers might have. Sure enough, there was some. Evidently the water pump had found some life during the night and was able to send some water up to the hillside tanks above us. I used it to its fullest. It was so nice to be clean.

It was also nice NOT to be a walking pile of ache, as I had expected. Not even my feet ached, though, and they ache on most days.

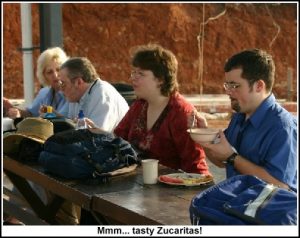

Breakfast was pancakes and more fresh fruit.

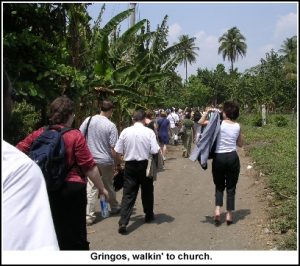

Afterwards, we held our morning bi-lingual devotional with Pastor Douglas, during which he talked about the need to call upon God’s help for our clinics that week. We also had prayer in Spanish and English for the doctors and medical staff who would be ministering to the physical needs of the patients and for the missionary staff who would minister to their spiritual needs.

We all knew what kind of stressful atmosphere we were about to go into—or at least we thought we did. At this point, I knew I was scarcely prepared for the job I’d been assigned and knew how much of a seat of the pants operation our set up would be. The night before, I’d been happy to leave the clinic site with no set up just because I was hot and tired, but that was looking like less of a good idea today. I was just hoping and praying that we could set up our pharmacy before the doctors could see too many patients and send them to overwhelm us. Whatever the case, I knew that we were doing God’s work and he would assist us and lend us strength to accomplish it. We just had to keep our faith. (Always easier said.)

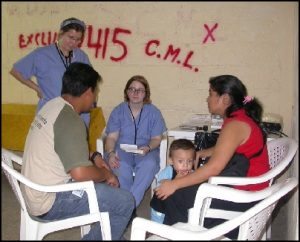

For our first week’s clinics, our WV team was originally to have three Osteopathic physicians, but one of them, Dr. Wadell, developed some rather nasty stomach problems days before the trip and was forced to stay home. We came with Dr. Allen and Dr. Lally. Assisting them would be three first year students (Carrie, Sarah, Dwan and J.C.). Our two fourth year medical students (my wife Ashley and her friend Flo) and third year med-student (Andrew) would be seeing patients on their own, consulting with the doctors as need be. The team from Wisconsin came armed with two dentists, a dental surgeon and several dental students. We also had two midwives, at least one nurse and a number of non-medical personnel, including Dr. Waddell’s wife Sandra and their daughter, plus the daughter of one of the dentists, quite a number of local missionaries and translators and one library assistant (i.e. me). All together our group was probably pushing 90 people.

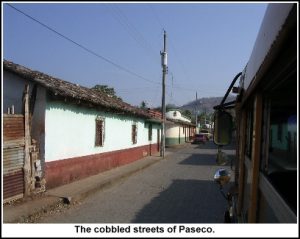

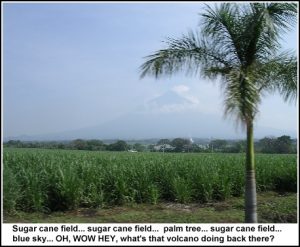

Our trip back to the bus-station took around 20 minutes. On the way, we passed probably 50 people who were either waiting by the side of the road for a ride or were walking along the edge of the road on their way to work. So many people in the area have to walk everywhere they go. Or catch rides in the backs of pickup trucks. I don’t think we saw a truck that didn’t have at least ten people in it the entire time we were there.

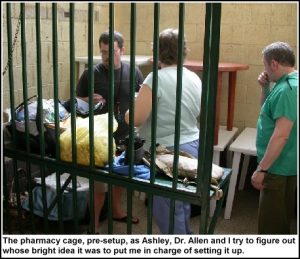

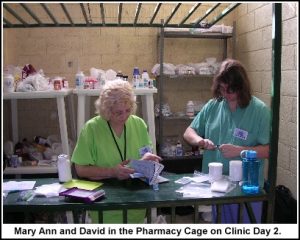

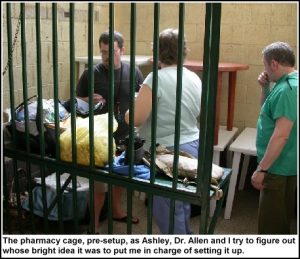

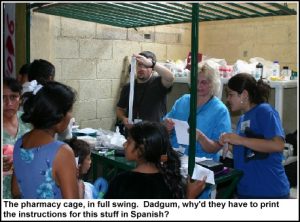

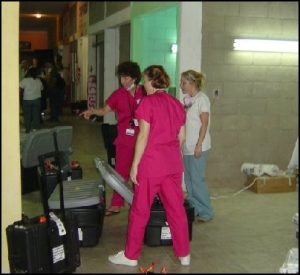

We arrived at the bus station clinic around 8 a.m. Mary Ann and I, already apprehensive and prayerful, were horrified to find that our little green jail cell of a pharmacy contained none of our requested shelving. We didn’t relish having to jump from duffel bag to duffel bag, rooting through bottles and baggies of pills to find the drugs we’d need for each prescription. We needed shelving! I started searching the bus-station for some shelves. I found a ready supply of plastic lawn tables with removable legs. These had been given to the entire team for our use. I figured two of them stacked would make for half-way decent shelving with room for storage beneath. Four of them were even better. Of course, it would be kind of difficult to reach the meds on the top tier in the back, but some shelves were better than no shelves. Still we had an awful lot of drugs to store, so taller shelving with more actual shelves was still needed. I left the pharmacy cage and began searching again.

We arrived at the bus station clinic around 8 a.m. Mary Ann and I, already apprehensive and prayerful, were horrified to find that our little green jail cell of a pharmacy contained none of our requested shelving. We didn’t relish having to jump from duffel bag to duffel bag, rooting through bottles and baggies of pills to find the drugs we’d need for each prescription. We needed shelving! I started searching the bus-station for some shelves. I found a ready supply of plastic lawn tables with removable legs. These had been given to the entire team for our use. I figured two of them stacked would make for half-way decent shelving with room for storage beneath. Four of them were even better. Of course, it would be kind of difficult to reach the meds on the top tier in the back, but some shelves were better than no shelves. Still we had an awful lot of drugs to store, so taller shelving with more actual shelves was still needed. I left the pharmacy cage and began searching again.

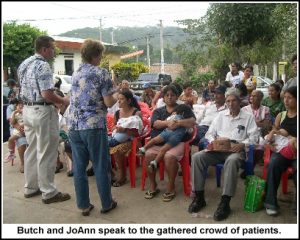

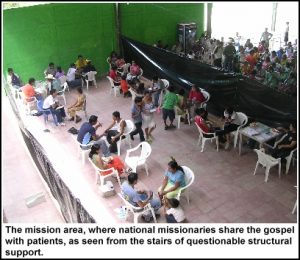

Before I could search very far, Butch came to tell us it was time to introduce the mission team to the crowd. Crowd? I hadn’t seen a crowd? Where was the crowd? Mary Ann and I left our shelf setup in the pharmacy cage and followed Butch, Dr. Allen and a number of other med-staffers down the long hall that made up the clinic proper and around the corner. There we found the rest of the mission team gathered for prayer. Afterwards we began filing through a doorway at the end of the corridor that led into the open market area of the bus-station where we found ourselves standing at the edge of several dozen locals seated in plastic lawn chairs. This was ostensibly the pre-waiting room for the clinic where the patients who arrived earlier and received a number card wait.

Before I could search very far, Butch came to tell us it was time to introduce the mission team to the crowd. Crowd? I hadn’t seen a crowd? Where was the crowd? Mary Ann and I left our shelf setup in the pharmacy cage and followed Butch, Dr. Allen and a number of other med-staffers down the long hall that made up the clinic proper and around the corner. There we found the rest of the mission team gathered for prayer. Afterwards we began filing through a doorway at the end of the corridor that led into the open market area of the bus-station where we found ourselves standing at the edge of several dozen locals seated in plastic lawn chairs. This was ostensibly the pre-waiting room for the clinic where the patients who arrived earlier and received a number card wait.

The way our medical mission clinic system worked was like this: potential patients arrived in the morning before the medical team. They were each issued a numbered card–essentially their “ticket” into the clinic–until all the allotted cards for the first half of the day had been distributed. (Probably 60 cards total. More cards were distributed later in the morning and even into the afternoon once it was clear what the patient turnover rate was and we could tell if there would be time in the day to see more patients.) At this point the patients were brought to the pre-waiting area where they are seated and eventually introduced to both the medical team and the mission team. One of the missionaries, usually Butch with Marcello translating, then explained the clinic/mission process. The patients were told how the entire med/mission team was there to minister to both physical and spiritual needs. On the physical side, the patients would be seeing doctors and the doctors would diagnose them and give them a prescription for medicine, all free of charge. The fact remained, though, that we could not give them a life-time supply of medicine and what we were able to give them would be gone within a month or so. However, the news of the gospel that the mission team was there to share did come in a lifetime and even after-lifetime supply. Every patient there would be given the chance to hear the gospel message. No one had to accept it or even listen to it if they didn’t want to. But every patient would be given the chance to talk one on one with a missionary. Regardless of their decision, they would still see a doctor and be treated. The missionaries were just there to offer more.

The way our medical mission clinic system worked was like this: potential patients arrived in the morning before the medical team. They were each issued a numbered card–essentially their “ticket” into the clinic–until all the allotted cards for the first half of the day had been distributed. (Probably 60 cards total. More cards were distributed later in the morning and even into the afternoon once it was clear what the patient turnover rate was and we could tell if there would be time in the day to see more patients.) At this point the patients were brought to the pre-waiting area where they are seated and eventually introduced to both the medical team and the mission team. One of the missionaries, usually Butch with Marcello translating, then explained the clinic/mission process. The patients were told how the entire med/mission team was there to minister to both physical and spiritual needs. On the physical side, the patients would be seeing doctors and the doctors would diagnose them and give them a prescription for medicine, all free of charge. The fact remained, though, that we could not give them a life-time supply of medicine and what we were able to give them would be gone within a month or so. However, the news of the gospel that the mission team was there to share did come in a lifetime and even after-lifetime supply. Every patient there would be given the chance to hear the gospel message. No one had to accept it or even listen to it if they didn’t want to. But every patient would be given the chance to talk one on one with a missionary. Regardless of their decision, they would still see a doctor and be treated. The missionaries were just there to offer more.

The only thing I really knew about the medical side of things was what I had heard from Ashley and from Dr. Wallace, (the physician who had been the medical team leader for Ash’s 2003 mission). Dr. Wallace contends that the only “real medicine” he ever gets to practice is when he’s doing mission work. When he’s in his office in the states, there are a myriad of do’s and don’t’s that restrict the way he can work. One naturally thinks of HMO’s and insurance companies and the many rules and regs associated with them, not to mention mal-practice insurance, but there are other pitfalls for the average doc too. For instance, if a doctor sees patients whose care is paid for through Medicare or Medicaid, that doctor is extraordinarily restricted in what he can do for any other patient he sees. Let’s say the doctor sees a patient who is not on Medicare and does not have insurance to pay for their treatment; that doctor might want to cut the patient a break and treat them for free, but under Federal regulations legally cannot do so because he or she accepts Medicaid patients. Cutting a non-Medicaid patient a break while seeing other Medicaid patients is tantamount to Medicaid fraud and the doctor could be fined incredible amounts of money. A doc can get around that by simply not accepting Medicaid patients, but then they would be cutting out a good portion of their patient base. That’s just one example of the kind of things physicians in this country have to worry about that they don’t in Central America.

On a medical mission, such rules and regs are pretty much thrown out the window. Such rules are not as strict in Central America to begin with. And if the mission doc sees a condition that needs treating then and there, he’s not going to refer the patient to another doc more specialized in taking care of it unless one happens to be standing within 20 feet at the time. Teeth get pulled, bones get reset, wounds get treated, medicines get prescribed and emergencies taken care of, all by the clinic docs. Basically, the job that needs doing gets done with no red-tape. (It’s how things used to work for family practice docs nationwide.) Granted, some things are beyond the scope of a medical mission staff and have been known to get shipped to the nearest emergency room, but for the most part if it walks in to the mission clinic it gets taken care of there.

As we were led out in front of the crowd and Marcello introduced the group of us in Spanish as the mission team. We then each took turns introducing ourselves to the patients, saying our name and what sub-group we belonged to. It felt very weird to say I was on the medical team, but that was my role for the week.

As we were led out in front of the crowd and Marcello introduced the group of us in Spanish as the mission team. We then each took turns introducing ourselves to the patients, saying our name and what sub-group we belonged to. It felt very weird to say I was on the medical team, but that was my role for the week.

I stood there in line with my fellow team-members and tried to be patient, but my mind was screaming at me that what I needed to be doing was setting up the pharmacy and finding shelves to aid in that search. I’d seen some shelves in a caged and locked cubby-hole shop before, but had been told they were privately owned and we could not borrow them. While I stood there before the crowd, at one end of the bus-station’s open air market, I spied at the other end of the market area a set of tall gray metal shelves. They were next to a cubby-hole shop that was actually open, but the shelves weren’t being used.

After the introductions were finished, Butch explained that the med team’s needed to leave to go prepare their stations. I made a dash for those shelves. They were perfect! Tall, metal and gray, about six tiers worth of shelving, seven if we used the top. However, I didn’t want to take them without permission. I tracked down Mrs. Hounko again and asked her about the shelves. They didn’t seem to be in use and were sitting out in the open where we could get to them. She said she would ask the manager of the bus station and see if we could.

Meanwhile, back at the pre-wating area, Dr. Allen had stayed behind to offer his testimony to the gathered patients. This was a daily occurrence during the clinics, with a different team member giving their testimony every day. Unfortunately, I wasn’t there for any of the testimonies the first week, because I was busy seeing to the pharmacy. During the second week, though, I did hear a few and found them very affecting. It’s always intriguing to hear how the people came to know Jesus. Often, they do so despite fighting against it for years. And it can be even more amazing when you knew the person before salvation and can see what a life-altering change is made following it. (My own testimony is very normal and not terribly exciting in this regard. I’ve had my share of on-again/off-again time with the lord, a problem that I still struggle with. I’ll probably share it before this blog has finished.)

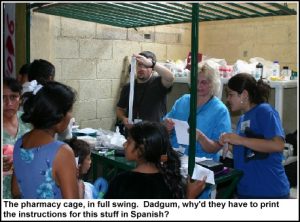

Mary Ann and Ashley were back in the pharmacy cage, assembling the tables I’d found into makeshift shelves. We began stocking these with meds, starting with the A’s. However, our luggage full of meds was not arranged in any particular order, let alone alphabetical, so there was much running and searching of bags to find what we needed. And we always found something we forgot to stock later and had to make space for it. Also, while many of our meds were of the pre-bagged variety, that we’d dosed out the night before, there were plenty of others that had not been counted and were still in big bottles. We just stocked those too and worried about the counting part later. We could see, though, that we were quickly running out of room on our make-shift patio table shelving. That was when Mrs. Hounko came to the rescue. She arrived with two gentlemen who carried in our requested metal shelves, set them up in the open corner of the pharm-cage and even wiped them off for us. We started shifting stock quick. Even with the shelves, though, we didn’t have room for all the meds, but after relocating our vast vitamin supplies to the floor, we felt like we were still in good shape.

During this chaos, the two people who were to be our primary pharmacy translators for the trip arrived. Their names were Cynthia and Esdras. Both looked to be in their late teens or early 20’s. We didn’t have time to chat much with them, though, because we were under deadline to get set up. They both chipped in to help us out and before long we had our makeshift pharmacy mostly set up, or at least as set up as it was going to get before our first patient arrived.

During this chaos, the two people who were to be our primary pharmacy translators for the trip arrived. Their names were Cynthia and Esdras. Both looked to be in their late teens or early 20’s. We didn’t have time to chat much with them, though, because we were under deadline to get set up. They both chipped in to help us out and before long we had our makeshift pharmacy mostly set up, or at least as set up as it was going to get before our first patient arrived.

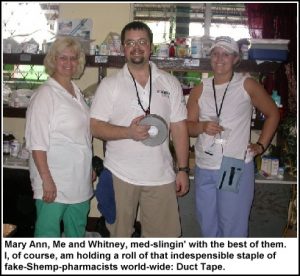

The job of pharmacist was pretty intimidating at first. As I said, I know little of pharmaceuticals beyond household painkillers, so I was initially terrified that I would make a massive screw up and do someone harm. However, I soon came to see that, for the most part, I didn’t really have to know anything about the drugs to do the job. Being a medical mission pharmacist mostly involved dispensing drugs as per doctor’s instructions as deciphered from cryptic dosage codes written in bad handwriting on the back side of each patient’s history sheet. It was also good that Mary Ann, my partner in med-slinging, is a nurse who knows from bad handwriting. She gave me further pointers by writing out some pharmaceutical codes for me to follow, that the doctors would be using.

qd = one pill per day

bid = two pills per day

tid = three pills per day

qid = four pills per day

hs = bed time (or hour of sleep)

There were also symbols for the quantity of pills to take with each dose, ranging from 1 to 3. These look like Roman numerals, without the bottom bar and with the addition of corresponding dots above the upper bar. As long as I could properly interpret these and other such instructions I was fine. And when I couldn’t, Mary Ann usually could. In extreme cases, we sometimes had to go track down the docs themselves to see what they meant, but usually we had it sussed out pretty good.

These codes were also easily transferred to our non-language based instruction slips we brought with us and which we included in each baggie of meds. The slips consisted of four panels featuring a face with a pill being shoved in its mouth. In each panel, there was also a time indicator, such as a sun rising for morning, sun at mid-day for noon, sun setting for evening or a moon for night. We’d circle the morning face for once a day, morning and night faces for one pill every 12 hours, three faces for a pill every 8 hours, and all four faces for every 6 hours. Beyond that, we also had Cynthia and Esdras conveying the dosing instructions in Spanish to help explain our circled cartoons. It was a simplistic way of doing things, but that’s what the job required. The docs were each seeing between 40 and 60 patients per day each, but we were seeing ALL of them. And when seeing hundreds of patients, you don’t have time to mess around with complicated instructions unless the instructions are actually complicated. We had our moments for that too.

For instance, some of the meds, such as Amoxyl, came in powder form and required mixing and refrigeration by the patients themselves. The amount of water to be added to the poweder was not measured in teaspoons, though, but 74 milliliters. So we had to mark medicine cups for them at the 30 milliliter and 15 milliliter marks and show them how they would have to pour two 30 milliliter amounts and one 15 milliliter amount, (Yes, I know, this makes 75 milliliters, but lets not pick nits), into the bottle and shake it all up. Then we had to mark the medicine cup for the 1/2 teaspoon amount of mixed medicine they would have to give to their child. This is where the translators Esdras and Cynthia became invaluable to us, because after we’d explained it to them only a couple of times, they knew exactly what to tell the patients and from there on out we just had to pass them a bottle of Amoxyl and say, “This is the Amoxyl/mixing/refrigeration speech,” and they’d go right to it.

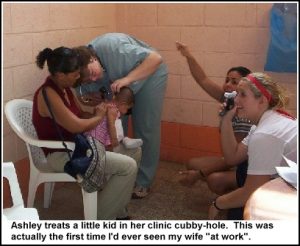

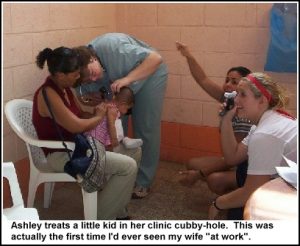

After only a handful of patients had come through, I started feeling more confident about the job. Ashley had stayed with us to help for the first 10 patients or so before being called away to start seeing patients herself. It was a little scary to me at first that she wasn’t there as our safety net, but I didn’t have much time to worry as more patients came flying at us. I tell you, having the experience of working Mondays at the library certainly prepared me well for the stress of the pharmacy cage that day. In fact, I daresay I’ve had worse days at the library. Just not for 12 hours straight.

After only a handful of patients had come through, I started feeling more confident about the job. Ashley had stayed with us to help for the first 10 patients or so before being called away to start seeing patients herself. It was a little scary to me at first that she wasn’t there as our safety net, but I didn’t have much time to worry as more patients came flying at us. I tell you, having the experience of working Mondays at the library certainly prepared me well for the stress of the pharmacy cage that day. In fact, I daresay I’ve had worse days at the library. Just not for 12 hours straight.

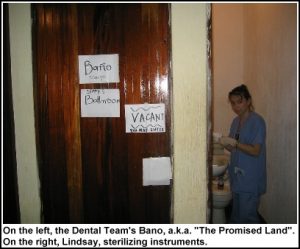

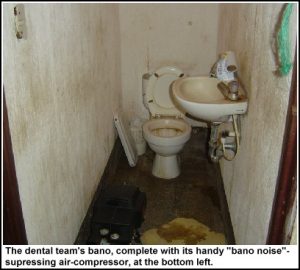

Even with only Mary Ann and I inside the cage, it was still terribly hot. I was sweating profusely and constantly wiping it away with my arms so as not to soil my hands. Eventually, I went and found a wash cloth to use as a sweat rag, and I carried it everywhere I went. When I did manage to soil my hands, I was very careful to wipe them down with my ready supply of hand-sanitizer before continuing with the pills. I also made frequent trips to the bano to wash them with soap and water and then more hand-sanitizer. The patients didn’t seem to mind that we were sweating. They were sweating too. It’s just one of the realities of being trapped in a cage in a sweltering bus-station. Before too long into the day, Marcello brought in a fleet of oscillating fans to set up at each medical station. Our pharmacy cage power outlet wasn’t working properly, though, so our fan had to be set up across the hall and pointed toward us. Unfortunately, most of the wind was blocked by the patients waiting for their prescriptions. The fan wasn’t entirely ours, either, as Ashley’s doctor station was two cubbies down from us and she needed air too, so the fan oscilated between us. We were all pretty uncomfortable.

Even with only Mary Ann and I inside the cage, it was still terribly hot. I was sweating profusely and constantly wiping it away with my arms so as not to soil my hands. Eventually, I went and found a wash cloth to use as a sweat rag, and I carried it everywhere I went. When I did manage to soil my hands, I was very careful to wipe them down with my ready supply of hand-sanitizer before continuing with the pills. I also made frequent trips to the bano to wash them with soap and water and then more hand-sanitizer. The patients didn’t seem to mind that we were sweating. They were sweating too. It’s just one of the realities of being trapped in a cage in a sweltering bus-station. Before too long into the day, Marcello brought in a fleet of oscillating fans to set up at each medical station. Our pharmacy cage power outlet wasn’t working properly, though, so our fan had to be set up across the hall and pointed toward us. Unfortunately, most of the wind was blocked by the patients waiting for their prescriptions. The fan wasn’t entirely ours, either, as Ashley’s doctor station was two cubbies down from us and she needed air too, so the fan oscilated between us. We were all pretty uncomfortable.

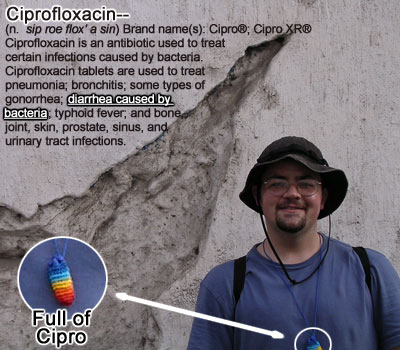

As I said, we still had pills that we needed to count out individually, because they had not been among those pills that were pre-dosed before. Mostly we had to do this with Naproxen Sodium and Cipro, two drugs that the docs were prescribing loads of. In some cases, like for children, the prescription required a smaller milligram dosage than the pills naturally come in. In such cases, we would have to cut the pills in half. Most of the time this was easy enough, as we did bring a pill splitter with us. The splitter only worked with round pills, though, so for long pills, like Cipro, we needed to use Mary Ann’s extry-sharp Swiss Army pocket knife. (It was a brand new knife, so it was clean!) I split those on a cutting board, cupping my hand over the pill as I cut it to prevent pieces from shooting out between my fingers. However, during one pill-cutting session, my cupped thumb wound up beneath the knife and when I chopped down on the pill it also chopped into my thumbnail, cutting into it at an angle from the tip down to about half an inch in. It didn’t hurt, but I immediately knew that I’d cut through the nail pretty deep. I was afraid I’d start bleeding, but other than a little blood beneath the nail, I was fine.

I was proud that, uncharacteristically for me, I didn’t start howling like a girl about my wound. I just slapped a Band-aid on it, acted like a real man and went back to my job. I became even more proud of this good behavior a few minutes later when a patient arrived at the pharmacy counter who had a wound far far worse than I pray I ever have or see again.

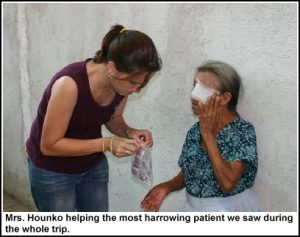

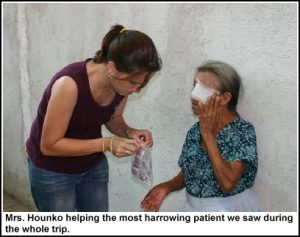

The wounded patient was a 73 year old woman, tiny, thin and frail-looking. She reminded me a lot of my Mamaw, only with long gray and black hair tied back in a pony-tail. She would have looked like any number of elderly patients we’d seen that day, but for one difference. Covering the right side of her face, around her eye, was a new white bandage that had been taped to her temples and brow. The woman had been led to us by Astrid, one the missionary translators who had been working with Dr. Allen that morning, who was holding on to the lady’s arm, steadying her and slowly guiding her to the counter of the pharmacy cage. (We didn’t yet know Astrid, but we would come to appreciate both her immense skills as a translator and her sweet spirit as the week progressed.)

The wounded patient was a 73 year old woman, tiny, thin and frail-looking. She reminded me a lot of my Mamaw, only with long gray and black hair tied back in a pony-tail. She would have looked like any number of elderly patients we’d seen that day, but for one difference. Covering the right side of her face, around her eye, was a new white bandage that had been taped to her temples and brow. The woman had been led to us by Astrid, one the missionary translators who had been working with Dr. Allen that morning, who was holding on to the lady’s arm, steadying her and slowly guiding her to the counter of the pharmacy cage. (We didn’t yet know Astrid, but we would come to appreciate both her immense skills as a translator and her sweet spirit as the week progressed.)

As the lady passed her prescription to us, I first noted that it was written for antibiotic cream. Then, out of curiosity, I looked back up at the lady to her makeshift eye patch. The bandage didn’t quite reach all the way to her nose, and at the edge of it there I could see that part of the side of her nose was actually missing, just above her nostril. It was a crescent shaped wound but you could see from the size of the bandage that the visible portion of the wound was only a tiny part of the whole and that it likely extended across her entire eye orbit, if not onto her cheek itself.

I was only a little bit shocked at the sight initially, not having time to really consider the ramifications of such a wound. The lady didn’t seem to be in any pain, however. So I shrugged it off and started filling her prescription for antibiotic cream.

Most of our cream meds were in large tubes, which we parceled out smaller amounts from in little mini-zip-lock baggies. However, most of our anti-biotic cream came in little individual sample packets. The prescription didn’t specify how much cream to dispense, but I knew that if she was meant to put it on that wound for any amount of time she would be needing a lot of it. I loaded up a baggie for her with cream-samples and gave it to her. She smiled and thanked us and Astrid led her away.

Only after she had gone did I begin to wonder what had happened to the lady that could have caused such a wound? My imagination went into overdrive on this. One thing was certain, though: I knew that I would never again complain about having to stand in a hot and sweaty cage with a little self-inflicted cut through my thumbnail. Such things no longer mattered. That poor lady was living through far worse and did so with a smile. We would learn far more about this lady that evening.

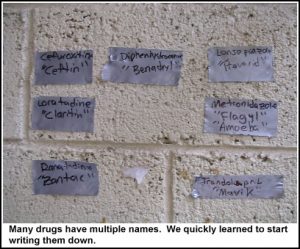

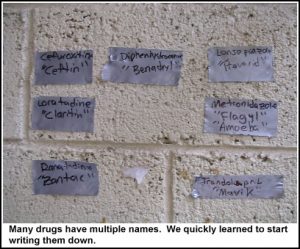

We didn’t have time to dwell on what we’d seen. More patients and more prescriptions came at us fast and we were having to scramble. We could mostly keep up with it and didn’t have huge lines until one of us would run into trouble with a particular prescription. Usually our trouble was that the doc who’d written it hadn’t specified something that needed specifying, like how many pills should the person take and how often. Other times the docs would use the drug-name for the drugs and not the commercial name (for instance Ranatidine instead of Zantac) and I’d have to figure out what they meant. This affected me more than Mary Ann, who almost always knew which was which. I still had to go around making little duct-tape labels of all the different double named drugs we were commonly prescribing. And in other cases, we simply couldn’t find the medicine at all either due to our having misplaced it among the shelves or not having unloaded it from one of the four suitcases and shipping cartons in the first place. These stock-cases were scattered in different places down the corridor and we’d have to run and dig through them all before finding it. One of them, we discovered, had been left on the bus, so I had to find Oswald and his “bus key,” a.k.a. Marcello’s daughter, to help me fetch it. It went on like that all day long.

We didn’t have time to dwell on what we’d seen. More patients and more prescriptions came at us fast and we were having to scramble. We could mostly keep up with it and didn’t have huge lines until one of us would run into trouble with a particular prescription. Usually our trouble was that the doc who’d written it hadn’t specified something that needed specifying, like how many pills should the person take and how often. Other times the docs would use the drug-name for the drugs and not the commercial name (for instance Ranatidine instead of Zantac) and I’d have to figure out what they meant. This affected me more than Mary Ann, who almost always knew which was which. I still had to go around making little duct-tape labels of all the different double named drugs we were commonly prescribing. And in other cases, we simply couldn’t find the medicine at all either due to our having misplaced it among the shelves or not having unloaded it from one of the four suitcases and shipping cartons in the first place. These stock-cases were scattered in different places down the corridor and we’d have to run and dig through them all before finding it. One of them, we discovered, had been left on the bus, so I had to find Oswald and his “bus key,” a.k.a. Marcello’s daughter, to help me fetch it. It went on like that all day long.

Just keeping up with the never-ending stream of patients bearing prescriptions was stressful enough. And even if I wasn’t going to complain about it, doing so under the conditions of heat, humidity and sweat made it even worse. In such an environment, tempers are apt to flare and I was afraid mine would be no exception to that. I’m well known in my house and sometimes at my place of employment for not dealing terribly well with stress. I have been known to growl and snarl and have on occasion been known to utter ear-blistering curses when under such stress. Oh, I keep it together pretty well during my solo Monday hell-shifts at the library, but prolonged exposure to such stress had me worried that I might crack. The entire mission team had been told to be on our best behavior and to always have a smile on our faces, because the locals would be watching us carefully. Here we were, ostensibly a group of Christians coming into towns to do work and help save souls. If we didn’t look the part, if we got angry or seemed unhappy at having to do the job that we’re doing, the locals would likely draw conclusions, maybe even correct conclusions, that we’d rather not have them draw. And I knew that the pharmacy was very important in this regard; after all, it would be the last impression most patients would have of our team and if we were short-tempered and growly, it would not be a good one. I had prayed at the start of the day for God to give everyone on the team strength in this regard, but especially me. I had known things were likely to get ugly and I wanted emotional backup from on high when it did. And I have to say that throughout the day, with very few exceptions, I remained blissfully calm and a smile—a genuine smile—was never far from my lips. I suppose I should not be surprised, for it was exactly what I’d prayed for. I think the entire team fell under this blanket of calm.

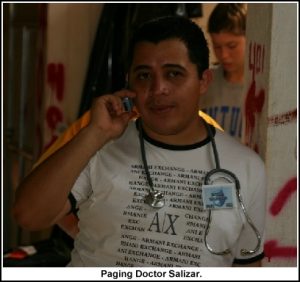

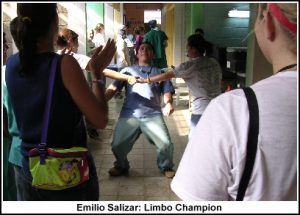

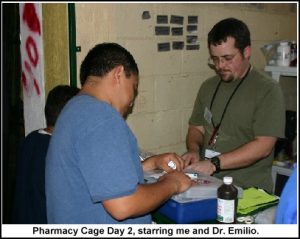

Another of the people on the medical team none of us had yet met was Emilio Salizar. Emilio was a 4th year medical student in Guatemala who looked like he was probably in his mid-20s. Sometime late in the morning he set up a clinic cubby-hole directly next door to the pharmacy. Emilio didn’t speak very much English, so we had to let Esdras do the introductions and interpreting. Much like my 4th year med-student wife, Emilio was there to see patients too. He had an advantage over the American docs, though, in that he didn’t have to have a translator on the patient end of things in order to do his job, so he was able to see far more patients far faster than most everyone else. The only real trouble came on our end, which is where the translation wound up shifting. Emilio would prescribe drugs with brand names we’d never heard of. And in Spanish. So most of the time we needed Esdras or Cynthia to translate the prescriptions before we could fill them. Often they would not be familiar with the drugs in question either and we’d have to go to Emilio himself and often consult Mary Ann’s PDA, which was equipped with Epocrates, a program for cross-referencing drugs and their international brand names. Emilio was wonderfully patient with us, especially the times he would come to ask us if we had a particular med and we’d just throw up our hands in classic “Beats me” pose. He would just grin and we’d start trying to help figure out what he needed. He became a familiar sight in the pharmacy during our clinics that week, often accompanying his patients, checking to see what meds we had on hand and then writing prescriptions right there. This didn’t bother us one bit. What ever it took to work things out was all fine with us.

Another of the people on the medical team none of us had yet met was Emilio Salizar. Emilio was a 4th year medical student in Guatemala who looked like he was probably in his mid-20s. Sometime late in the morning he set up a clinic cubby-hole directly next door to the pharmacy. Emilio didn’t speak very much English, so we had to let Esdras do the introductions and interpreting. Much like my 4th year med-student wife, Emilio was there to see patients too. He had an advantage over the American docs, though, in that he didn’t have to have a translator on the patient end of things in order to do his job, so he was able to see far more patients far faster than most everyone else. The only real trouble came on our end, which is where the translation wound up shifting. Emilio would prescribe drugs with brand names we’d never heard of. And in Spanish. So most of the time we needed Esdras or Cynthia to translate the prescriptions before we could fill them. Often they would not be familiar with the drugs in question either and we’d have to go to Emilio himself and often consult Mary Ann’s PDA, which was equipped with Epocrates, a program for cross-referencing drugs and their international brand names. Emilio was wonderfully patient with us, especially the times he would come to ask us if we had a particular med and we’d just throw up our hands in classic “Beats me” pose. He would just grin and we’d start trying to help figure out what he needed. He became a familiar sight in the pharmacy during our clinics that week, often accompanying his patients, checking to see what meds we had on hand and then writing prescriptions right there. This didn’t bother us one bit. What ever it took to work things out was all fine with us.

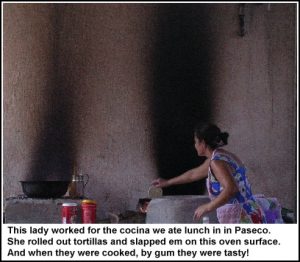

Around 12:30 it was time for lunch. Since there were so many patients still waiting, we didn’t want to shut down the whole clinic for lunch so we were going to take it in shifts. Mary Ann volunteered to go second shift so she could eat with her husband, so I was to take first.

Lunch was served a few doors down from the bus-station itself, at what appeared to be an outdoor bar next to the local fire-station. We had a choice of either chicken sandwiches or hamburgers. My burger was pretty good, though I did notice the presence of a mysterious pink sauce on it that seemed to be a condiment. Our theory, upon later discussion, was that this was the Guatemalan version of “special sauce”, i.e. Thousand Island dressing. Only the ketchup to mayonnaise ratio seemed skewed more toward ketchup, making it pink instead of Thousand Island-colored. This would not be the last time I would meet this particular sauce during my time in Central America.

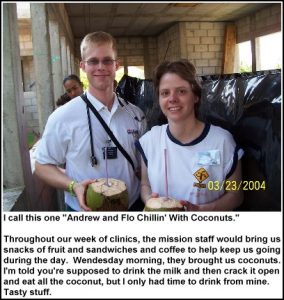

I didn’t hang around long after I’d finished eating. Though I did want a break, I knew the pharmacy was bound to be busy and Mary Ann would need relief. I also knew that once she and Dr. Allen went to lunch, the traffic would drop off considerably due to the fact that Dr. Allen wouldn’t be pumping patients through like the pro he is. And on this theory, I was right. Things slowed right down. I had time to talk to Esdras and Cynthia between prescriptions. Esdras gave me pointers on my Spanish. I’d been using a little that day, saying things like “Uno por dias” and “Dos por dias” for pill amounts to take. Esdras pointed out that I should actually be saying “Uno por DIA” as it was one per day and not days.

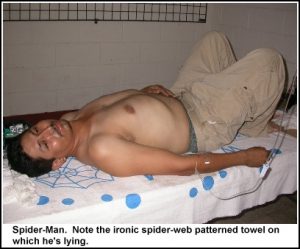

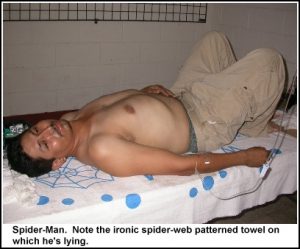

After Mary Ann & Dr. Allen returned from lunch, the clinic had its first emergency case of the day. It began with raised voices looking for Dr. Allen. I didn’t find out the details until later, but the emergency case was a man with a possible spider bite or scorpion sting on his leg. The wound had occurred some days before and had begun to redden and began to develop into cellulitis, an infection of the skin itself. The man had taken some Amoxicilin for it, which is an anti-biotic that’s available over the counter in Guatemala, but it’s not the right kind of anti-biotic to treat cellulitis, so the condition worsened. All the while he continued going to work, getting sicker by the day as the cellulitis infection spread through his bloodstream and made him septic until he collapsed that morning. When they brought him in he was burning up with

After Mary Ann & Dr. Allen returned from lunch, the clinic had its first emergency case of the day. It began with raised voices looking for Dr. Allen. I didn’t find out the details until later, but the emergency case was a man with a possible spider bite or scorpion sting on his leg. The wound had occurred some days before and had begun to redden and began to develop into cellulitis, an infection of the skin itself. The man had taken some Amoxicilin for it, which is an anti-biotic that’s available over the counter in Guatemala, but it’s not the right kind of anti-biotic to treat cellulitis, so the condition worsened. All the while he continued going to work, getting sicker by the day as the cellulitis infection spread through his bloodstream and made him septic until he collapsed that morning. When they brought him in he was burning up with  a fever, dehydrated, delirious and unable to move his arms properly. Dr. Allen began treating him with a drip IV and came to us for liquid anti-biotics and other anti-biotic pills. Cooling him off was definitely part of the treatment too because at one point Butch came over and asked if he could borrow our fan. He said they needed it for a guy who was dying.

a fever, dehydrated, delirious and unable to move his arms properly. Dr. Allen began treating him with a drip IV and came to us for liquid anti-biotics and other anti-biotic pills. Cooling him off was definitely part of the treatment too because at one point Butch came over and asked if he could borrow our fan. He said they needed it for a guy who was dying.

“Yes! Please! Go! Take it!” I said. I’m thinking, Don’t ask for the fan–just take it! He’s dying!

The man lived, but from what Dr. Allen said later it was a close thing and he might not have been out of the woods entirely. The man lay on a makeshift cot for much of the day until he finally woke up and by the end of the day he seemed pretty coherent as he walked the halls with his IV.

In the afternoon, Butch came to take my camera. Before joining Word of Life, he used to work for an IT department and is thus a fully wired dude of much computer savvy. He had brought his laptop, a speaker system and a video projector. (Butch was also never ever out of proximity to his PDA, on which he kept our daily clinic stats, syncing it up with the laptop every day.) Butch’s master plan was to collect all the digital cameras from the staff and download their pictures onto his laptop to save to DVD later. This way everyone on the team could have a copy of everyone’s pictures. It was a great idea.

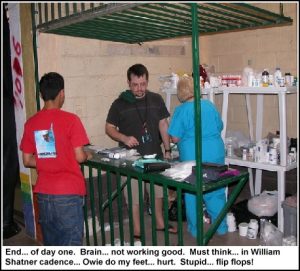

Right around 4:30, my brain stopped working. It evidently had decided it had had enough activity for the day and was no longer going to function at peak capacity. The result of this was that I could no longer think clearly and everything I did took twice as long because I kept having to stop and refocus my brain on the task at hand. I thought maybe I was just dehydrated, so I chugged down some more water. Nope. Brain just stopped workin’ right. Of course, this is when we became the busiest.

Right around 4:30, my brain stopped working. It evidently had decided it had had enough activity for the day and was no longer going to function at peak capacity. The result of this was that I could no longer think clearly and everything I did took twice as long because I kept having to stop and refocus my brain on the task at hand. I thought maybe I was just dehydrated, so I chugged down some more water. Nope. Brain just stopped workin’ right. Of course, this is when we became the busiest.

Cynthia and Esdras dove in to help us out with the rush. By that time in the day, they’d seen most of what we were dispensing and knew the dosage amounts to circle almost better than we did. They jumped behind the counter and started dispensing, being certain to confirm with one of us that what they were doing was right. I never saw them make a mistake.

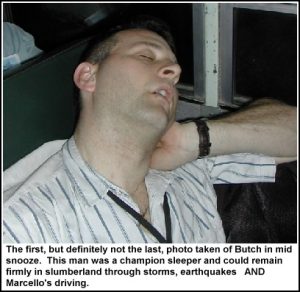

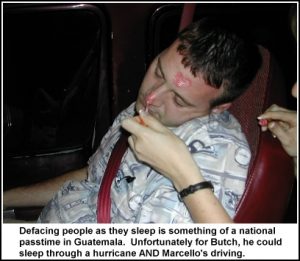

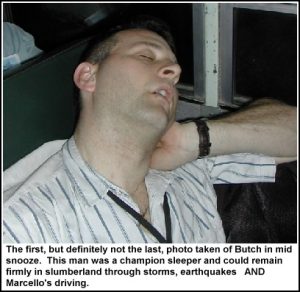

We were supposed to shut down the clinic at 5, but everyone knew this was an arbitrary deadline to be ignored. If we still had patients in the hopper to see, we’d stay until they were seen. The docs kept working and we kept dispensing until 7:30 p.  Even after the last patient received their meds, we couldn’t really relax. So much of our medicine still needed counting and pre-dosing and we’d even run out of some of the dosed meds and would have to count out more from the stock supplies. We knew we’d have to haul a chunk of it back to camp to do later and after the draining day we’d already had, this thought nearly exhausted us. We proved this on the way back to camp, as several members of the team fell right to sleep, including Butch. Dr. Allen snapped his photo to give to Dr. Rich, who had fallen asleep at the church dedication the day before and had been photographed by Butch.

Even after the last patient received their meds, we couldn’t really relax. So much of our medicine still needed counting and pre-dosing and we’d even run out of some of the dosed meds and would have to count out more from the stock supplies. We knew we’d have to haul a chunk of it back to camp to do later and after the draining day we’d already had, this thought nearly exhausted us. We proved this on the way back to camp, as several members of the team fell right to sleep, including Butch. Dr. Allen snapped his photo to give to Dr. Rich, who had fallen asleep at the church dedication the day before and had been photographed by Butch.

We got back to camp around 8 and learned that the water pump had been replaced during the day so the showers were running at full capacity. Yay! The transformer was still having issues, but as long as we only ran the one air-conditioner per cabin, we’d be okay. Sounded like heaven to me.

I dumped my stuff at the cabin and came down for dinner. Butch was at the pavilion setting up the slide show, going through and rotating the images so that everything was upright. He used a freeware slide-show program that allowed him to play the slides with music. The first song up was “Let my Words be Few” by Phillips, Craig & Dean. It’s a beautiful song and fit right in with the images that began flashing up on the screen above. I sat down to watch, seeing images of the medical team and dental team doing their jobs. Only then was I really struck with the incredible nature of what had taken place that day. Oh, sure, I had known in a kind of On Paper way that the mission was doing a lot of good, but I’d been trapped in the cage all day and had seen very little of the treatment, except on occasional bano breaks. Seeing it on the screen really brought it home and I knew that I had taken part in something far greater than myself.

I dumped my stuff at the cabin and came down for dinner. Butch was at the pavilion setting up the slide show, going through and rotating the images so that everything was upright. He used a freeware slide-show program that allowed him to play the slides with music. The first song up was “Let my Words be Few” by Phillips, Craig & Dean. It’s a beautiful song and fit right in with the images that began flashing up on the screen above. I sat down to watch, seeing images of the medical team and dental team doing their jobs. Only then was I really struck with the incredible nature of what had taken place that day. Oh, sure, I had known in a kind of On Paper way that the mission was doing a lot of good, but I’d been trapped in the cage all day and had seen very little of the treatment, except on occasional bano breaks. Seeing it on the screen really brought it home and I knew that I had taken part in something far greater than myself.

Then the slide clicked over to a shot of the lady with the eye wound—only without her bandage covering it. As bad as I had imagined that wound to be from just the little glimpse I’d had of the edge of it, the reality was far far worse. Her entire ocular orbit was simply missing, from just above her nostril across her cheek and to the brow ridge. Gone. It looked like something you wouldn’t believe in a horror movie, yet there it was in full color. It was too much for me. The weight of the day fell on me hard and I began sobbing uncontrollably. I felt so very sorry for that poor old woman with half of her face missing. What had caused that? Dear, God, what had caused that? And all we had been able to do for her was give her a baggie of anti-bacterial cream.

Then the slide clicked over to a shot of the lady with the eye wound—only without her bandage covering it. As bad as I had imagined that wound to be from just the little glimpse I’d had of the edge of it, the reality was far far worse. Her entire ocular orbit was simply missing, from just above her nostril across her cheek and to the brow ridge. Gone. It looked like something you wouldn’t believe in a horror movie, yet there it was in full color. It was too much for me. The weight of the day fell on me hard and I began sobbing uncontrollably. I felt so very sorry for that poor old woman with half of her face missing. What had caused that? Dear, God, what had caused that? And all we had been able to do for her was give her a baggie of anti-bacterial cream.

I couldn’t take it. I walked away from the pavilion and into the darkness, down the hill toward the lake, and I just cried and cried. I had known my emotions had been close to the surface all afternoon, but now I couldn’t control them at all. I just stared into the darkness with tears streaming down my face while Phillips, Craig and Dean sang, “Jesus, I am so in love with you. And I stand in awe of you, Jesus.” And I found myself in awe. Surely there had to be some greater purpose in this woman’s life. Maybe she was meant to live as an example of goodness in the face of such a woeful injury. But what a price! It absolutely broke my heart.

I prayed then for the old woman. I prayed that God would take her home rather than let her suffer. Or if that was not his will, that God would make her the example of a beautiful soul shining through the tragedy that I hoped she already was. I just wanted her to have blessings in this life and to gain her deserved reward in the next. It was one of those moments in life that seem so incredibly unfair and make you wonder how God could allow such a thing to have happened. But the thing about God is, he knows what he’s doing. He has a plan and it will be carried out in his good time. That may sound like excuse-making to non-Christians, but I’ve seen it happen and I prayed that I had seen it in that lady’s face that day.

After ten minutes or so, I was out of tears. I could see Ashley sitting back at one of the tables beneath the pavilion lights. I wiped my face and went back up to sit beside her. She wasn’t in much better shape than me, emotionally, but she had a glorious smile on her face through the tears as she watched the slides from the day. She could see it too; the good that had been done by just a few people.

Later, Dr. Allen told us about the old woman. He had treated her. She is in her early 70’s and had received a burn to the eye from hot oil nearly 15 years ago. Her eye couldn’t be saved then and without medical care the surrounding tissue, starved of blood by the burns, began to slowly necrose. The wound has continued to increase in size since then and she was in horrible pain for many years because of it. But eventually, the nerves that were in the area died out and for the past two years she has had no pain from the wound at all. She keeps it very clean and washes it out every day. She had not even come in to the clinic seeking treatment for the wound itself, but simply wanted to know if we could give her a bandage to cover it because she didn’t like how it looked. Dr. Allen said he loaded her up with bandages.

I continued to be emotional throughout the evening, but I was far from the only one. As Butch read the stats of the day to us, we learned that the clinic saw over 500 patients that day and 117 of them accepted Christ, with many others reaffirming their existing faith. The medical treatment is definitely the draw that gets people in, but clearly some leave with much more. We had to give that an “Amen!”

We were up later than we wanted to be with our evening devotional, but we knew it was important. It was a time for people to share things they had seen throughout the clinic day and give thanks. The translators and local missionary staff seemed impressed at the energy of the medical team. We too were impressed by theirs. It may not seem like it would take much energy to translate languages, but it can be brain-taxing work. From all reports, the translators are fantastic and I already knew that ours were.

Afterwards, starting at 9:30 or so, we began the arduous task of pill sorting and counting once again. I really didn’t want to be there. I so wanted to go to the showers and then climb into bed, but I knew we had to keep plugging away or tomorrow would be far worse. Second day at any clinic setting is always busier than the first, because word gets out and word of mouth spreads fast. We had to have these things pre-counted or we’d be forever counting pills the next day. We had lots of volunteer help from the medical and dental team. As we started to work, Butch kept his laptop going and began showing funny little video clips he’d been collecting for years. The videos really lightened the mood and made the work go faster. I was still dog-tired, but at that moment I just felt great that we were laughing and continuing to work toward a larger goal that was bigger than any of us.

GUATEMALA CLINIC DAY 1 STATS

Patients Seen: 525

Prescriptions Filled: 330

Salvations/Rededications: 114

NEXT

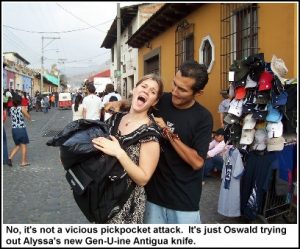

The driver of our bus was a man called Oswald. We would come to respect him greatly as both a person and a driver over the week, but our initial impressions were that he was a bit reckless. Driving regulations in Guatemala are a good deal more lax than in the states. I’m sure they have laws to cover it, but most of the time they don’t seem to be enforced. Oswald proved that point by hurtling our massive bus through busy city streets, weaving among the cars like an Indy driver, as we made our way out of town. And while it might have seemed reckless at first, we soon came to realize that Oswald had a great deal of skill when it came to maneuvering that bus. He was aided in this by one of the missionary staff named Alex. Alex was a funny man who was able to convey his humor despite his rusty English skills. Alex’s job was to lean out the door of the bus and make sure Oswald wasn’t running over anything important. They made a great team and no important things were squooshed.

The driver of our bus was a man called Oswald. We would come to respect him greatly as both a person and a driver over the week, but our initial impressions were that he was a bit reckless. Driving regulations in Guatemala are a good deal more lax than in the states. I’m sure they have laws to cover it, but most of the time they don’t seem to be enforced. Oswald proved that point by hurtling our massive bus through busy city streets, weaving among the cars like an Indy driver, as we made our way out of town. And while it might have seemed reckless at first, we soon came to realize that Oswald had a great deal of skill when it came to maneuvering that bus. He was aided in this by one of the missionary staff named Alex. Alex was a funny man who was able to convey his humor despite his rusty English skills. Alex’s job was to lean out the door of the bus and make sure Oswald wasn’t running over anything important. They made a great team and no important things were squooshed.