Clinic Day 3

I decided to go out and scout around the camp a little Wednesday moring to take some more pictures. Even though I had been at the camp for over two days, I had not really had a good look at the place. This time I walked down the in-progress stone drive/walk way all the way to the lake where I got some gorgeous shots of the sunrise over the still surface of the water. A few minutes later, the net fisherman returned, far across the lake, and began casting their morning nets. There were mango trees all along the edge of the lake. As I walked near to one, a mango fell from high in the tree and hit the ground with a tremendous smack that sounded like it would have hurt had anyone been on the receiving end. I’m continually amazed at this country and the fruit trees that are everywhere.

I decided to go out and scout around the camp a little Wednesday moring to take some more pictures. Even though I had been at the camp for over two days, I had not really had a good look at the place. This time I walked down the in-progress stone drive/walk way all the way to the lake where I got some gorgeous shots of the sunrise over the still surface of the water. A few minutes later, the net fisherman returned, far across the lake, and began casting their morning nets. There were mango trees all along the edge of the lake. As I walked near to one, a mango fell from high in the tree and hit the ground with a tremendous smack that sounded like it would have hurt had anyone been on the receiving end. I’m continually amazed at this country and the fruit trees that are everywhere.

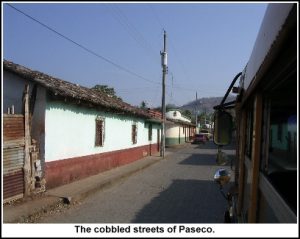

Our new clinic site was in the town of Pasaco, which Marcello told us was about five minutes from camp. The last time we’d heard any destination was 5 minutes from camp, it turned out to be 20 minutes from camp. This time it was only ten minutes, though, so we thought Marcello’s Gringo-Time guestimation was improving.

Pasaco was a tiny but very pretty and picturesque town. It didn’t feel as urban as Chiquimuilla did and there was not as much traffic. We were thankful for this, as there felt like barely enough room for our busses. I was again amazed at Oswald’s ability to maneuver ours through such tiny streets. The more we rode with him the more we loved him. Oswald seemed like a pretty cool cat too and never failed to say “Ereek” whenever I boarded his bus. There was some debate around this point in the journey as to whether his name was Oswald or Oswalt. Finally, Ashley asked him point blank and he said that it’s pronounced Oswald, “like the name of the man who killed President Kennedy.” Ah. This, however, would not be the last mystery we would encounter with Oswald’s name.

Pasaco was a tiny but very pretty and picturesque town. It didn’t feel as urban as Chiquimuilla did and there was not as much traffic. We were thankful for this, as there felt like barely enough room for our busses. I was again amazed at Oswald’s ability to maneuver ours through such tiny streets. The more we rode with him the more we loved him. Oswald seemed like a pretty cool cat too and never failed to say “Ereek” whenever I boarded his bus. There was some debate around this point in the journey as to whether his name was Oswald or Oswalt. Finally, Ashley asked him point blank and he said that it’s pronounced Oswald, “like the name of the man who killed President Kennedy.” Ah. This, however, would not be the last mystery we would encounter with Oswald’s name.

The clinic site was in the Palacio (city hall), located on what looked to be Pasaco’s town-square. There was a decorative tower in the middle of the square, surrounded by a grassy fenced park where roosters strutted. Along the edges of the square were cocinas (restaurants) and shops and a beautiful white church. There was also a long line of wrecked vehicles. (Looking back on the photos, it might have been fun to make jokes about them having been the first several cars owned by Marcello, but at the time I was still two days away from learning the true terror that is Marcello’s driving.)

The clinic site was in the Palacio (city hall), located on what looked to be Pasaco’s town-square. There was a decorative tower in the middle of the square, surrounded by a grassy fenced park where roosters strutted. Along the edges of the square were cocinas (restaurants) and shops and a beautiful white church. There was also a long line of wrecked vehicles. (Looking back on the photos, it might have been fun to make jokes about them having been the first several cars owned by Marcello, but at the time I was still two days away from learning the true terror that is Marcello’s driving.)

The Palacio itself was the seat of Pasaco’s government not to mention the police station for the area. The building was under quite a bit of construction at the time, as they were trying to add a second floor onto the existing first floor. Therefore, there was a lot of exposed rebar and concrete block work to be seen. Our team was pretty much given the run of the entire building and Marcello had already worked out where most of the clinic stations would be located within it.

The Palacio itself was the seat of Pasaco’s government not to mention the police station for the area. The building was under quite a bit of construction at the time, as they were trying to add a second floor onto the existing first floor. Therefore, there was a lot of exposed rebar and concrete block work to be seen. Our team was pretty much given the run of the entire building and Marcello had already worked out where most of the clinic stations would be located within it.

Our new pharmacy was to be located inside the police chief’s personal office, which was the first office in a corridor that split off about mid-way down the Palacia’s main hallway. Further down our side corridor was the office of the mayor and another city-governmental office. Then, directly across the main hallway from our corridor was another corridor that lead to two large multi-person offices where the dental team would set up. The Palacio’s main hallway lead further into the building itself, where it opened on a very large area, like a garage or recreational area, painted green. This was where the pre-waiting room and mission area would be set up. From the large green area there were other rooms off to the left where Dr. Allen, Ashley and Andrew would have their clinic area and a set of somewhat scary looking but ultimately sturdy concrete steps that lead to the still under construction second story where the pediatrics ward would be housed.

Our pharmacy office was very neat and tidy and was a far bigger space than the cage we’d been in before. It also came with three desks, offering plenty of space for counting pills and not getting in each other’s way too much. It didn’t, however, have much in the way of usable shelving. Fortunately, we’d planned ahead.

That morning during breakfast, Dr. Allen and Ashley had hit upon the notion that since we didn’t know what kind of shelving we could expect, we should bring our own in the form of two of the wooden benches that were set up on either side of our meal-tables. The benches were probably twelve feet in length and, if stacked, would give us two twelve foot long shelves with space beneath. We’d hauled them over in Oswald’s bus and found that they worked perfectly when stacked atop two of the office’s desks. Brilliant! We ran to find all of our alphabetically sorted bags and began loading up the shelves and desks with meds. Clinic setup was pretty simple after that.

That morning during breakfast, Dr. Allen and Ashley had hit upon the notion that since we didn’t know what kind of shelving we could expect, we should bring our own in the form of two of the wooden benches that were set up on either side of our meal-tables. The benches were probably twelve feet in length and, if stacked, would give us two twelve foot long shelves with space beneath. We’d hauled them over in Oswald’s bus and found that they worked perfectly when stacked atop two of the office’s desks. Brilliant! We ran to find all of our alphabetically sorted bags and began loading up the shelves and desks with meds. Clinic setup was pretty simple after that.

We decided that we would not allow patients into the office itself, but that we would bring their finished prescriptions out to them. To this effect, we set up a fourth small desk in the corridor outside where it backed up against the closed half of the gated doorway that lead into the main hall and we strung a rope across the open other side. Our plan was to let the patients line up along the hallway and we could take their prescriptions. Esdras would mostly be stationed at the desk in the hall to translate for us.

We decided that we would not allow patients into the office itself, but that we would bring their finished prescriptions out to them. To this effect, we set up a fourth small desk in the corridor outside where it backed up against the closed half of the gated doorway that lead into the main hall and we strung a rope across the open other side. Our plan was to let the patients line up along the hallway and we could take their prescriptions. Esdras would mostly be stationed at the desk in the hall to translate for us.

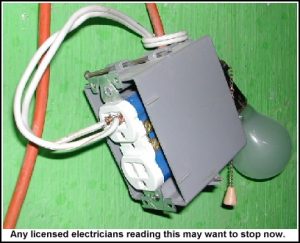

The weather was still very hot and the building was pretty much an open windows affair like the last one. However, we had the added advantage of having four, count `em 4, fans in the Pharmacy Office. FOUR! Frankly, we were embarrassed to have so many because we really only needed one, maybe two, for the office itself and one for Esdras in the hallway. So throughout the day, we kept trying to give away our extra fans, but we got no takers because there were so very few power  outlets in the building that there was often no place to plug them. We’d already exhausted our outlets with power-strips and had extension cords running out the windows to bring power to other areas of the complex. And even then, we kept running over the cords with the office chairs and unplugging them, which must have driven Esdras crazy in the hallway to have his fan keep cutting out. He never said a word, though, and I found myself keeping watch over the cords and fans to make sure they were all running smoothly and he could get air.

outlets in the building that there was often no place to plug them. We’d already exhausted our outlets with power-strips and had extension cords running out the windows to bring power to other areas of the complex. And even then, we kept running over the cords with the office chairs and unplugging them, which must have driven Esdras crazy in the hallway to have his fan keep cutting out. He never said a word, though, and I found myself keeping watch over the cords and fans to make sure they were all running smoothly and he could get air.

I think the drugs we dispensed the most throughout the two weeks of mission clinics were vitamins. We brought an enormous supply of them too, being as we knew we would need a lot and so that’s one of the drugs we primarily asked for donations for. It’s a good thing we had them too.

I think the drugs we dispensed the most throughout the two weeks of mission clinics were vitamins. We brought an enormous supply of them too, being as we knew we would need a lot and so that’s one of the drugs we primarily asked for donations for. It’s a good thing we had them too.

We had a huge supply of children’s chewable vitamins, most arriving in standard drug-store sized bottles, but others having been donated by our local pharmacist that came in giant Sam’s Club style pill bottles. We also had a ready supply of adult vitamins and prenatal vitamins. The prenatals came as sampler packets from the drug companies, usually little round blister cards of 5 pills each. Before leaving for the trip, our local team members had held a packing party to get everyone’s supplies packed and weighed and we had used that time to divide up the prenatals and put six of these 5 pill cards into sandwich baggies for a month’s dose. These were kept in a giant black suitcase that was nearly bursting with them. Unfortunately, we didn’t get to dispense many of them during the first week because we had only a few pregnant women come through the clinic. However, the children’s and adult vitamins went out with nearly every prescription.

The local people are huge believers in the power of vitamins. Our doctors found that the patients thought that just about any ailment they might have could be cleared up with a strong application of vitamins. So when they asked for vitamins, they got vitamins, in addition to the other more effective medicines they really needed. As Dr. Allen explained to us, medicine is often more art than science, and if a patient believes something is going to help them they will often get better despite how much that drug may be inappropriate to treat their condition. So Dr. Allen tended to prescribe both the effective drugs and the ineffective ones, figuring one or the other would do the trick.

The local people are huge believers in the power of vitamins. Our doctors found that the patients thought that just about any ailment they might have could be cleared up with a strong application of vitamins. So when they asked for vitamins, they got vitamins, in addition to the other more effective medicines they really needed. As Dr. Allen explained to us, medicine is often more art than science, and if a patient believes something is going to help them they will often get better despite how much that drug may be inappropriate to treat their condition. So Dr. Allen tended to prescribe both the effective drugs and the ineffective ones, figuring one or the other would do the trick.

The only major trouble with this plan is that kids LOVE the taste of vitamins, and you couldn’t give the vitamins directly to the kids or they would be dashing away popping them like candy. So we had to give them to the parents and explain to them that the kids were to take no more than “Uno Por Dia.” Often, the parents would nod and then hand the baggie right to the kids, who would dash away and likely consume them all. (I didn’t actually witness any child doing this, but Ashley did on her previous trip.)

Now, it’s not such a bad thing for a kid to eat a month’s supply of run of the mill chewable vitamins. It’s not ideal, but they’ll process them okay. However, some children were iron deficient and required a children’s vitamin with iron. Most over the counter Flintstones chewables don’t come equipped with Iron, so we brought a different brand that did and stored them in a totally separate location and bottle from the regular children’s vitamins and had not pre-dosed them because we did NOT want any confusion. A kid takes too much Iron at once and bad things can happen. So we had Esdras stress and explain the importance of keeping the vitamins with Iron away from the children except for one per day and told the parents that it would make their kids sick if they ate any more than that. Then we prayed they had listened.

Unfortunately, as the prescriptions started coming in on Wednesday, we discovered that all but our prenatal vitamins were missing. Not that they’d been taken, or anything. They simply hadn’t been among the meds in the bags we had located and were therefore still in one that we hadn’t. I left the pharmacy and scouted around all the other clinic areas to find it. Trouble was, I wasn’t sure I had been the guy to pack them and didn’t remember what their bag looked like.

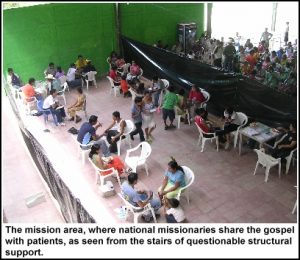

As I was starting my search, I passed by the mission area, which was situated on the other side of a wall in the Palacio’s garage. It had close to 15 pairs of plastic chairs set up where members of the mission team sat. Those people from the waiting area who wanted to hear more about the gospel than just the message Pastor Douglas preached and the testimony given earlier by Andrew, could go and speak one on one with one of the missionaries. I’d not seen the missionary area in Chiquimuilla, except in photographs, but this one was amazing. The missionaries who were there talking to the patients all beamed with joy as they shared the gospel message. And while I expected to find more patients who were unwilling to listen or who might be there simply for the medical treatment and going through the motions, I didn’t see that at all. The response I could see on their faces was genuine and touching.

As I was starting my search, I passed by the mission area, which was situated on the other side of a wall in the Palacio’s garage. It had close to 15 pairs of plastic chairs set up where members of the mission team sat. Those people from the waiting area who wanted to hear more about the gospel than just the message Pastor Douglas preached and the testimony given earlier by Andrew, could go and speak one on one with one of the missionaries. I’d not seen the missionary area in Chiquimuilla, except in photographs, but this one was amazing. The missionaries who were there talking to the patients all beamed with joy as they shared the gospel message. And while I expected to find more patients who were unwilling to listen or who might be there simply for the medical treatment and going through the motions, I didn’t see that at all. The response I could see on their faces was genuine and touching.

After asking around about vitamins to little effect, I finally went into the dental area where I eventually found them. Turns out the bag had been lumped in with the dental team’s things and then stored under a table to get it out of the way.

I made a few mistakes early in the day in the pharmacy and was unhappy about it. Nothing major, but definitely a miscalculation on my part. My big actual screw up of the day came later. We’d received what I thought was a standard prescription for a Amoxyl. I marked a medicine cup appropriately and asked Esdras to give them the Amoxyl speech, for the standard 250 mg 1 teaspoon dose. Unfortunately, after the patient had been instructed and had left the clinic, Mary Ann discovered that the prescription had actually called for a half teaspoon dose. This is one of the real troubles with not being a real pharmacist and trying to play one—when most drugs are pre-dosed, you have to pay strict attention when the docs sta

rt calling for different dosages. You also have to pay attention to the age of the child, as reported on the patient history, which might indicate to you to look for a smaller dose. Naturally, I didn’t take this screw up on my part very well. I was, in fact, mad about it, both at

myself for having been lax in my observations and at Dr. Allen for not marking things clearer so that non-pharmacists such as myself had a better chance at catching such changes. In reality, he’d marked it perfectly clearly, but a pharmacy as busy as ours tends to fall into a fast-food assembly line mentality when so many of the same things are ordered. Following that metaphor, once in a while, you’ll get an order for a burger with no onions and you have to be ready for it. It was a good lesson to learn and, fortunately for the child in question, not one that would result in anything more serious than a little diarrhea. This was not the first nor the last time that things would get screwed up due to my efforts.

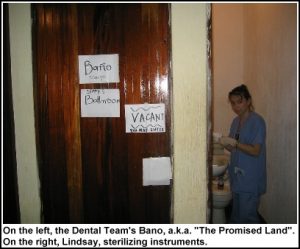

One thing I might have had good reason to be cranky about was the bano situation. In the Palacia, there were a limited number of banos available. Two of them were side by side at the far end of the dental wing corridor. However, one of the was being used for sterilization of instruments while the other had a PRIVATE MISSION TEAM RESTROOM sign on the door as well as an OCCUPIED/EMPTY sign. The only other bano that I knew about was in the mayor’s office, which was further down the corridor that the pharmacy was located on. The mayor had made himself scarce for the duration of the clinics, but we’d been told we could use his bano.

One thing I might have had good reason to be cranky about was the bano situation. In the Palacia, there were a limited number of banos available. Two of them were side by side at the far end of the dental wing corridor. However, one of the was being used for sterilization of instruments while the other had a PRIVATE MISSION TEAM RESTROOM sign on the door as well as an OCCUPIED/EMPTY sign. The only other bano that I knew about was in the mayor’s office, which was further down the corridor that the pharmacy was located on. The mayor had made himself scarce for the duration of the clinics, but we’d been told we could use his bano.

As far as Central American bano’s go, his was not atypical, but it was also not ideal. For one thing, the door didn’t have a handle on the inside and would stick tight in its frame when closed. Once inside, therefore, you had no guarantee of getting out until someone heard your screams for help. For another, while the toilet did “work” and the sink did “work”, there was enough water (dear, Lord, I prayed it was water) on the floor to suggest something was leaking somewhere. And while there was also soap at the sink, the hand-drying towel was filthy enough that you didn’t really want to touch it, let alone dry anything on it. Being as how this was one of the only banos available, though, it was used by just about everyone at some point in the day.

As far as Central American bano’s go, his was not atypical, but it was also not ideal. For one thing, the door didn’t have a handle on the inside and would stick tight in its frame when closed. Once inside, therefore, you had no guarantee of getting out until someone heard your screams for help. For another, while the toilet did “work” and the sink did “work”, there was enough water (dear, Lord, I prayed it was water) on the floor to suggest something was leaking somewhere. And while there was also soap at the sink, the hand-drying towel was filthy enough that you didn’t really want to touch it, let alone dry anything on it. Being as how this was one of the only banos available, though, it was used by just about everyone at some point in the day.

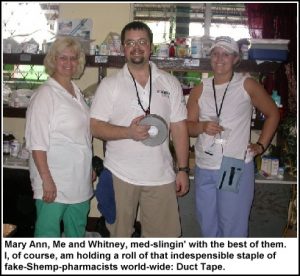

We didn’t have David to assist us in the pharmacy that morning, but we did have help from Whitney, the 18-year-old daughter of one of the mid-wives on the WV portion of the team. If she hadn’t done mission pharmacy work before, she sure took to it pretty quickly.

We didn’t have David to assist us in the pharmacy that morning, but we did have help from Whitney, the 18-year-old daughter of one of the mid-wives on the WV portion of the team. If she hadn’t done mission pharmacy work before, she sure took to it pretty quickly.

My Spanish skills, while not near conversational, were starting to get better and I was starting to recall more of what I’d learned in college. Edsras gave me some more pointers and graciously corrected me when I messed up. So, instead of saying “Uno por dia” or “Dos por dias” to patients, I had graduated to “Dos diarias.” I felt like I sounded like I knew what I was saying, but I must have been speaking with a foreign accent because many patients gave me a confused look when I tried Spanish on them.

I spoke with Esdras some more about his future plans. He’d mentioned an interest in computers the day before and how one day he might like to come to the states to go to college to do more with them. I ask him how that process might work. He said that mostly it’s very difficult for Guatemalans to get visas to study in America. And when it is possible, there is a lot of bureaucratic red tape to wade through. He asked what school might be good to attend for computer training. I told him that Mississippi State University, my alma mater, had a decent computer science department. Plus Mississippi is hot and humid too, so if he was able to go there it would be a lot like living at home.

We had a sudden rush around lunch-time and even though Whitney and I had been told to go on the first lunch shift, I didn’t feel like I could leave Mary Ann in the lurch like that. Then to our rescue came David H., our erstwhile 16-year old pharmacy vet from yesterday. He agreed to stay and help Mary Ann so we could go eat.

Lunch was at a little cocina across the square. There were tables out front, but we’d been told to go into the cocina itself, which meant walking through the kitchen of the cocina (or, the kitchen of the kitchen) and into the covered patio/cooking area in back. The smells were exactly the kind of smells you want to have coming out of a Central American cocina—all refried beans and meat and tortillas and guacamole. I caught sight of some of that sort of fare too and was looking forward to it.

Lunch was at a little cocina across the square. There were tables out front, but we’d been told to go into the cocina itself, which meant walking through the kitchen of the cocina (or, the kitchen of the kitchen) and into the covered patio/cooking area in back. The smells were exactly the kind of smells you want to have coming out of a Central American cocina—all refried beans and meat and tortillas and guacamole. I caught sight of some of that sort of fare too and was looking forward to it.

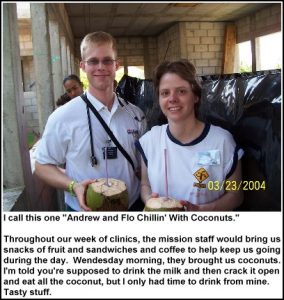

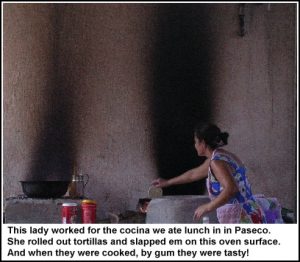

On the patio in back there were more tables and the familiar faces of the mission staff, including Ashley. This would be our first time to eat lunch together since Sunday. I sat down and we soon began a table-wide discussion of all the fabulous food we could see on other people’s tables and how we were looking forward to having some. We also watched one of the ladies who worked there as she prepared food by an enormous oven near the far wall. She was grinding cornmeal dough between two rocks, then slapping patties of it on the large concave oven surface to bake into tortillas. Aw, man, did we want some of that action!

On the patio in back there were more tables and the familiar faces of the mission staff, including Ashley. This would be our first time to eat lunch together since Sunday. I sat down and we soon began a table-wide discussion of all the fabulous food we could see on other people’s tables and how we were looking forward to having some. We also watched one of the ladies who worked there as she prepared food by an enormous oven near the far wall. She was grinding cornmeal dough between two rocks, then slapping patties of it on the large concave oven surface to bake into tortillas. Aw, man, did we want some of that action!

Then our waitress came out and brought us each a ham & cheese sandwich topped with mystery sauce on white bread, some french fries and a tray of lettuce, tomatoes and fruit. We all looked down at our plates, then over to the food on the plates of the local customers and collectively thought, “We don’t want this. We want some of what they have.”

Not that we were ungrateful Gringos, or anything, because the ham sandwiches and fries were good. We just hoped that by coming to Central America we would be able to sample more of the local faire. The ladies in the kitchen back at the camp were great cooks and had given us kind of a sampling of local dishes, which were all very very good. However, we could never be certain that they weren’t just feeding us what they thought Gringos wanted to eat. We wanted real uncensored Central American food. Sure, we understood that eating what the locals ate might kill us, or make us at least wish we were dead, but frankly if it meant I got to eat the tortillas and beans I could see, I figured it might be worth it.

We must have looked pitiful as we slowly gnawed on our ham & cheese sandwiches, stealing coveting glances at the food around us. And someone must have eventually taken pity on us, because after ten minutes or so our waitress brought out a basket of piping hot tortillas, a plate of refried beans, some sour cream and soft local cheese. We all dove in without pausing for consideration and greedily feasted on what were probably the best beans and tortillas I’ve ever eaten. (Later, Emilio would tell me that what we had eaten really wasn’t very good, as such things go, and that there was far better out there. Could’ve fooled me, though.)

I relieved Mary Ann and David to go to lunch. And since Dr. Allen and some other doctors went with them, things naturally slowed down for us in the pharmacy, leaving me and Esdras to hang out waiting for the occasional prescription.

Another translator came up after a while bearing a Guatemala City newspaper. I thought he was bringing it in to show the latest football scores to Esdras, but he’d actually brought it for me. He turned it to the international news section and pointed out the main story which was about the school shooting in Red Lake, Minnesota. Esdras translated much of the story for me, explaining that the kid’s father had shot himself four years earlier and his mother was in a mental institution. I was afraid this sort of thing might happen. Not a school shooting, per se, but a big news story back home that I might or might not hear about until I get back, if even then. It reminds me of the three week theatre camp I used to attend in high school and was staff at through college. Every year, something would happen in the world or major world figures or celebrities would die and I would never know about it until seeing them in a year-end retrospective because I’d been in a three week news vacuum.

As sad as that news was, I was happy that our translators thought to let us know about a situation back home that they thought we would need to know about. Esdras wanted to know how a kid that young could get hold of the kind of weapons he did. Not knowing any details of the case, I could only guess that they were his father’s old guns. But I pointed out that with a dad that killed himself and a mom in a mental institution, this poor kid had a lot of bad stuff going against him. I’m certainly not making excuses for what he did, because that was horrible and nothing could justify it. I’m just saying, with family life like that it’s hard not to loose a few screws yourself.

While I had the newspaper out, I turned it to the comic-strip page. In addition to local and regional cartoons I wasn’t famliar with, there were quite a few of the usual American comic strips, in Spanish. Esdras translated Garfield for me, but it didn’t make sense to me.

While I had the newspaper out, I turned it to the comic-strip page. In addition to local and regional cartoons I wasn’t famliar with, there were quite a few of the usual American comic strips, in Spanish. Esdras translated Garfield for me, but it didn’t make sense to me.

Must be funny in Spanish.

Around 3:30, or so, Marcello came into the pharmacy and told us that the chief of police wanted some medication. The meds the chief wanted didn’t amount to anything huge. I think the man basically had frequent headaches and needed a bottle of Ibuprofen or something. It wasn’t as though he wanted to take a stock bottle, or anything. However, Mary Ann wasn’t dispensing pill one without a prescription and told Marcello that the chief would need to see a doctor like everyone else.

Around 3:30, or so, Marcello came into the pharmacy and told us that the chief of police wanted some medication. The meds the chief wanted didn’t amount to anything huge. I think the man basically had frequent headaches and needed a bottle of Ibuprofen or something. It wasn’t as though he wanted to take a stock bottle, or anything. However, Mary Ann wasn’t dispensing pill one without a prescription and told Marcello that the chief would need to see a doctor like everyone else.

Now, I really don’t know anything about Central American law enforcement other than what I’ve seen in movies or read about in books. However, what I’d seen and read lead me to believe that denying the chief of police a handful of pills was not a good idea. Again, I could be wrong, but my impression was that Central American law enforcement works a bit differently than in the states and that its officers, particularly the leaders, are used to getting freebies and “tips” and having people do what they say. (Actually, that’s not really that different than how it sometimes works in the states, but it’s not how it’s supposed to work in the states.)

Part of me would love to have been there to see the chief’s face when Marcello explained that not only had we taken over his police station and kicked him out of his own office for two days, but we weren’t giving him any medicine either. Had to be a sight. I wasn’t really worried that the chief would do anything to us or kick the whole team out of the Palacia—after all we were there with the mayor’s blessing. It did still seem of questionable wisdom to turn him down like that, though.

I think Marcello realized pretty quickly he wasn’t getting through Mary Ann. But instead of having the chief stand in line like the rest of the patients, Marcello did an end-run around the issue and just went straight to Dr. Allen with the request. Dr. Allen wrote up a prescription and brought it to us himself and the chief got his baggie of pills.

The chief wasn’t the only person who was getting sick, though. Racine dental student Alyssa, always a bright and sunny young lady, was feeling mighty low too. It was probably a combination of the heat and maybe dehydration, but she got so sick she nearly passed out and Marcello had to send her back to camp to lie down.

At 4:30, right on time, my brain kicked out once again, but I didn’t feel nearly as worn out as at our other two clinics. Maybe this was because we had a plethora of fans on hand to keep us cool, but I just didn’t feel so bad. Things kind of slowed down a bit by then and I was able to go and sit with Esdras and some of the other translators and missionaries who had finished up their tasks for the day and had come to hang out. One of them called me “Doc” at one point and I had to correct him, “No es doctoro.” The last thing I wanted was to be mistaken for a doctor or to seem like I was trying to pretend I was a doctor in anyone’s eyes.

At 4:30, right on time, my brain kicked out once again, but I didn’t feel nearly as worn out as at our other two clinics. Maybe this was because we had a plethora of fans on hand to keep us cool, but I just didn’t feel so bad. Things kind of slowed down a bit by then and I was able to go and sit with Esdras and some of the other translators and missionaries who had finished up their tasks for the day and had come to hang out. One of them called me “Doc” at one point and I had to correct him, “No es doctoro.” The last thing I wanted was to be mistaken for a doctor or to seem like I was trying to pretend I was a doctor in anyone’s eyes.

One of the translators asked me what sports I liked. I had to admit that I don’t follow sports at all, except for the Super Bowl, which I usually watch if only for the commercials. I told him that I did play Soccer when I was a kid, but nothing since. He seemed to like this, since soccer (football) is huge in Guatemala and, in fact, the Guatemalan national team was about to play in a major championship two days from then. The translator then asked me what I thought of a particular well-known player, who he named. Of course, I’d never heard of the player. I think the translator was quietly appalled that such a sports-ignorant creature as myself could be walking the earth, but he grinned and rolled with it well-enough.

We wrapped things up around 6:30 for our first day in Pasaco and headed back to camp. We wouldn’t need any more pills counted, but we had run low on a few key items. Our supply of Ranatidine (Zantac) was near its end, as was our supply of cough syrup.

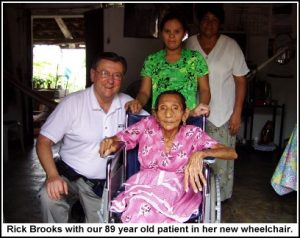

Back at camp, during our evening meeting, we learned from Doctor Allen that he had left the clinic briefly to deliver the new wheelchair to the 89-year-old patient from Tuesday. When they arrived at her house, they found the lady waiting for them in her best dress. She was overjoyed with her new chair and cried and cried with them and they with her. She just kept thanking them and praising God. These are the kind of experiences I didn’t get to see much of while I was locked away in the pharmacy, but I’m happy to report them here. I really should have done this blog as a team project with one of the docs, (except that the docs don’ t tend to have a lot of time for blogging. Well, except this one, maybe).

Back at camp, during our evening meeting, we learned from Doctor Allen that he had left the clinic briefly to deliver the new wheelchair to the 89-year-old patient from Tuesday. When they arrived at her house, they found the lady waiting for them in her best dress. She was overjoyed with her new chair and cried and cried with them and they with her. She just kept thanking them and praising God. These are the kind of experiences I didn’t get to see much of while I was locked away in the pharmacy, but I’m happy to report them here. I really should have done this blog as a team project with one of the docs, (except that the docs don’ t tend to have a lot of time for blogging. Well, except this one, maybe).

We also learned from one of our key missionaries that the mayor of a different nearby town had traveled to Pasaco to see what this clinic thing was all about and to see a doctor himself. He didn’t ask for special treatment, but joined the other patients and was witnessed to by this particular missionary. The missionary knew who the mayor was, and was a bit nervous about sharing the gospel with such a locally powerful man at first. But he soldiered on and gave the message. The mayor listened and was moved by the missionary’s words. And at the end, when the missionary asked if the mayor would like to accept Christ into his life, the mayor responded that yes, he would. Right there, the missionary lead the man through the prayer of admitting that he was a sinner and that he believed Jesus was God’s son sent to die in our place so that we might achieve salvation. The missionary was amazed and pleased at the mayor’s acceptance and the mayor, for his part, just beamed with joy over it. After he’d seen a doctor and been treated, he promised that he would return to his town and tell everyone of the work we were doing and encourage them to come.

Alyssa, our sick dental student, was at the evening meal and meeting too. She said she was feeling better. After the meeting, Ashley helped her out by performing some OMT (Osteopathic Manipulation Techniques) on her. OMT is similar in nature to the manipulative techniques of Chiropractic medicine. However, Chiropractic originated as part of Osteopathy, not the other way around as many people assume. It also offers a wider range of manipulative techniques than Chiropractic, though I’m sure the point might be argued by Chiropractors. (Keep in mind, I’m certainly not knocking Chiropractic medicine, which I think is great stuff. It’s just that Osteopathic medicine has a wider range.) The basic premise of both is that your body is designed to operate best when your bones and joints are in their proper alignment. If they get out of alignment, the works can get gummed up and all sorts of bad things can happen. So Ash’s OMT was essentially trying to make sure Alyssa was firing with all cylinders. She said it helped.

I also had my own after-meeting duties to attend to in the form of washing clothes. Due to the fact that we had limited space in our luggage for clothing, Ashley and I only brought a few changes of clothes. I had probably four t-shirts, three pairs of shorts, a pair of corduroy slacks, a pair of blue-jeans, undies and a few pairs of socks. By Wednesday, much of my gear was quite soiled and stinky with the weeks’ wear. I’d been stashing it in the vacuum-seal bag I’d used to transport it, so it wouldn’t stink up the cabin, but now that bag was getting full. I needed to do laundry and, as there were no official laundry facilities, I would need to use some Woolite and good old fashioned elbow grease. Ash poured some of her Woolite into an empty water bottle for me and I headed up to my cabin. Unfortunately, I was also too tired and had too little space to hang things up to do my entire load of laundry. I woundup doing a few essentials, such as my T-shirts and undies. I washed them out in one of the bano sinks and hung them up around my bed to dry.

Dr. Rich thought this looked like a good idea too, but he preferred to use a bucket for his laundry, so he went out in search of one. When he came back, he said he’d gone down to the kitchen and asked one of the ladies there if he might borrow a bucket.

“She looked at me like I was speaking English,” Dr. Rich said.

GUATEMALA CLINIC DAY 3 STATS

Patients Seen: 420

Prescriptions Filled: 463

Salvations/Rededications: 163