The Talkin’ Grad-u-mation, Hide the Presents, No Hints, Floral Prints, Stupid Cat Blues (a Non-Horrible, Horribly True Tale)

As you may know by now, I have a bit of difficulty in keeping surprises a surprise when it comes to my wife.

Oh, I try. I really do. But she almost always knows I’m planning something for her major celebratory days (birthday, anniversary, Christmas, etc.) and starts pestering me for hints weeks in advance. And like a moron, I always think, “This time I’m really gonna pull it off. She’ll never guess this hint.” Then, as though she’s plucked it from my very mind, out she comes with the answer, pissing me off and causing me to vow never again to give her any hints. Then the next birthday comes along and there I go lobbing hints like softballs at the Near-Sighted-Middle-School-Girl’s Little League Playoffs.

After my defeat last October—in which I entirely failed to keep secret the fact that her birthday present was me finally hauling away our old washing machine, freeing up valuable space in the dining room—I became determined that I was finally gonna get one past the batter.

My three opportunities to do so, barring any unforeseen emergency holidays, were Christmas, our anniversary and Ashley’s med-school graduation present. Christmas was right out, because by the time I thought of a really good and perfect present December had already passed. That left our 5th anniversary in early February and graduation in late May. I aimed for Feb.

And as to the perfect present… Oh, it was just too good.

A couple of years ago, while browsing in a nearby gallery of community art, Ashley fell in love with a painting by local artist Jeanne Brenneman. It was a floral watercolor entitled Flower Tower. Beyond the beauty of the flowers depicted, though, the construction of the painting and frame was nearly as intriguing. Mrs. Brenneman had taken an eight-inch-square piece of rough hand-made watercolor paper, the kind with craggy crinkly edges, and glued it to a larger piece of watercolor paper, also with cool craggy edges. Atop these layers, she painted the watercolor floral scene, and a most beautiful one at that. Then she mounted the whole thing on a thin piece of foam core which she in turn mounted to a matte board, framed by another matte board but with enough space that the viewer could see this painting floating above the back-most board, and then the whole thing was sealed in a wooden outer frame. It was beautiful work. Ashley thought it was fantastic. She immediately declared her undying love for the painting and threatened to buy it right there. Then she saw the price tag and we realized we could neither justify nor afford dropping several hundred dollars for it, no matter how much we loved the painting. And while the artist herself was known to do prints of her existing work, a print of this picture, no matter how well-rendered, could never match the original three-dimensional work.

Deciding not to buy this painting was a harder thing to do than we thought, though. We went back to the hall more than once just to look at the painting. And then, several months later, Ashley tracked down Mrs. Brenneman’s website, discovered the painting was again on display in another town and we drove nearly an hour to go see it. Once again, though, we could not justify its purchase. Not with two cars in need of repair and rent in need of being paid. We’d have to save such extravagances for the future, like maybe in 2039, after we’ve paid off the school loans.

As distant a purchase as that seemed, the idea of the painting and the memory of how much Ashley loved it stuck in my head and then resurfaced in January when I was brainstorming presents for our 5th anniversary. I decided to look into it. And while I still couldn’t really justify buying the painting as a whim purchase, I was—with a careful application of rationalization—able to justify purchasing it for a major event.

So I sent Mrs. Brenneman an e-mail explaining who I was, which painting I was interested in, and that I was interested in purchasing it as a surprise present for either our then upcoming 5th anniversary or for Ash’s graduation. Was it still on the market? Mrs. Brenneman soon wrote me back and said that it was indeed still on the market, but had been submitted for inclusion in an upcoming painting competition and would possibly be unavailable until late April. This was fine with me, as it helped me decide when I was going to give it to Ashley. What I liked even better was that her asking price for the painting was at least a full $100 less than I remembered it cost before. Win win.

After this, I just had to start saving cash. I stashed away bits and pieces from paycheck to paycheck as well as my entire payment for some freelance web design work I had done. My nest egg grew, safely hidden away. (I knew it was safe cause Ashley knows I never have any money, so she doesn’t go looking for it.)

Meanwhile, I knew I had to come up with some way to keep hint-beggar Ashley off my back. May was quickly approaching and the closer we got to it the more likely she would start asking what my plans were. To the rescue came my mother-in-law. She e-mailed me to ask if I would like to go in on a family graduation present of some black pearl jewelry that she hoped to persuade Ash’s grandmother and sisters to join in for. I said it sounded like a fine gift, but I opted out citing my own plans.

“Don’t give her any hints!” Ma warned. Evidently Ma didn’t tell that to everyone else in her little cabal. Within a week, Ashley came to me and told me that she knew there were some sort of group plans afoot. Apparently, her grandmother had spilled that much, though she hadn’t spoiled any surprises.

“Oh, really?” I said, trying to act innocent, which I knew Ashley would interpret as guilt.

“You know about it, don’t you?!”

“Mayyyyybe.”

“Gimme a hint!”

“Nope. I can’t say a word about it,” I told her. “This is something other people are working on, so I can’t give any hints.”

“Aw, c’mon! Just one hint.”

“No!” I shouted. I then further distanced myself from any hint-giving by speaking exclusively to the cat for the next 20 minutes.

The spoilage of Ma and Company’s surprise was a blessing in disguise, though. So long as I continued to deny everything and not give any hints, Ashley seemed satisfied that I was in cahoots with them and left me alone about any solo plans I might have. And so the days passed.

Since January, I’d kept in contact with Mrs. Brenneman and had continued to let her know I was still planning to make the purchase of her painting. We set a date, to meet at my library workplace to make the exchange, and soon our agreed upon date of May 26 had arrived. My co-workers were all in on the surprise by then and were sworn to secrecy.

Mrs. Brenneman arrived at exactly the time she said she would, painting case in hand. We chatted a little about the painting, the awards that it had won and her general creative process for it. Then, I filled out a bill of sale form she had brought, made a copy of it for her and made the purchase. The painting was now mine and soon it would be my wife’s. I just had to find a good place to hide it.

I left work in the early afternoon on Thursday and headed home. Ashley’s parents had already arrived, but had taken her out for lunch, leaving me the run of the house. My plan was to hide it somewhere inconspicuous-yet-accessible so I could sneak out late Friday night and hang it up somewhere in the house. After abandoning a few bad ideas, I opted to hide the painting behind the door to my office. The door is always open and would be difficult to close even if I wanted to due to the runner carpet wadded up in front of it. Seemed perfect. I even gave the room a few walk-by passes from the hall to make sure it didn’t attract my eye. Seemed good to me.

That night, Ashley, Ma, Pa and I went to the big awards banquet at Ashley’s school. This is the traditional ceremony where all the students and their families come and feast from a banquet buffet while the school’s faculty congratulates them for surviving all the way to graduation. A number of students are recognized with scholarship awards and the sashes and cords for the top 10 percent grade achievers are passed out. (Ash wasn’t among the top 10 percent, but she’s not far from it. Frankly, passing medical school at all is the major achievement. And like the old joke goes: Question– What do you call a student who graduates from medical school with a GPA of 70? Answer– Doctor.)

Ashley had brought along a manila folder, which I thought was a little odd, especially after she became real secretive about it when I asked what it contained.

About mid-way through the awards ceremony, the dean of students stood and announced she was about to award the American Osteopathic Foundation’s Donna Jones Moritsugu Award, an award given to an non-student individual who has demonstrated “immeasurable support” of a student enrolled in the medical school and to the Osteopathic profession at large. The candidate for the award is chosen from several such candidates and voted upon by the faculty of the school itself. In addition to a beautiful framed plaque, the award came with a check for $240. And when the dean announced the winner of the award, she called my name.

I was stunned. I never knew such an award existed in the first place, nor would I have expected to win it if I had. I suppose, that I wouldn’t have been surprised to have been a candidate, after all I was the co-president of the school’s spouse/significant other support organization for a year and helped out at the school in other ways. But primarily, the award was granted for helping support my wife as she went through the four years of schooling. In other words, I was given the award for being a good husband. How many men get to say they were given an award (one that came with cash) for being a good husband? Not many, I’d wager.

After the ceremony, on our way to the car, Ashley revealed what she had in the manila envelope. She had intended to open it and distribute its contents during the ceremony, but no such opportunity was officially offered. What it contained were were two printed citations, one for Ma and Pa and one for me. They had the official school seal and signature of the president of the school, and stated that they were given as a token of her sincerest gratitude for supporting and encouraging her efforts during school. The award was given as thanks for patience and love and being an integral part of her success. This single paper meant more to me than the framed one I’d just received inside. And it was at that moment that I decided I would give Ashley her present earlier than I’d intended.

My original plan had been to keep her painting a surprise all the way until Saturday morning. I was planning to sneak out and hang it up on an existing nail during the night and let her discover it when she got up Saturday. There on Thursday night, though, I felt such gratitude for the award she’d just given me that I wanted to rush home and give the painting right then. This was an urge I was able to fight off, though. I’d worked far too hard to keep this thing under wraps to give in quite that easily. However, I didn’t think it would hurt to give it to her a day early.

That night, just after we had retired for the evening, I got up to go fill my bedside water bottle and grabbed the painting from its hiding place on the way down the hall. I took down an existing frame on one wall of our living room, hung the new painting up, filled my bottle and then stashed the old frame behind the office door on my way back to bed. We went to sleep.

Early in the morning, our cat began driving us crazy. Usually we let her out in the evening, when she can run around in the dark and feel relatively safe from the entire lack of big bad animals that don’t stalk and kill her during the day. However, she didn’t get to go out in the evening because she was too scared that Ma and Pa might stalk and kill her if she came out from hiding. So at 5 in the morning, she began making a pest of herself, jumping on and off the bed and running up and down the halls at full speed, making as much noise as possible, in an effort to anger us to the point that we hurl her from the house.

“I better go let the cat out,” Ashley said, groggily.

“I can do it,” I said, fearing that she would see her surprise on the way through the living room.

“No, I got it,” she said, rising and snatching up the cat. I prayed silently that she wouldn’t notice her gift hanging on the living room wall, only a few feet from the back door, but figured that it wouldn’t be so bad if she did. She didn’t see it, though, and came right back to bed.

When we finally got up for good, around 7, I followed her into the kitchen. I had wondered how long it would take for her to notice it. I’d even envisioned the possibility that she wouldn’t notice it and would leave for her school-related functions that morning. Nope. Within 30 seconds of entering the kitchen, she turned, caught sight of it, turned away then did a double-take as her brain registered what she had seen. Her mouth dropped open and she said, “Ohhhhh.” Then she stared across the room at the painting for a long time, her eyes welling up with tears, then turned and smiled at me. The reaction was so satisfying. It was worth every bit of sneaking and plotting and secret-keeping on my part.

“How long have you been planning this?” she asked.

“Months,” I said.

“And he kept it a secret all this time!” Ma crowed triumphantly on my behalf. “He finally got one on you!”

“He did,” Ash said, giving me a big kiss. “He finally did.”

Copyright © 2005 Eric Fritzius

DATELINE: Saturday, April 2, 2005

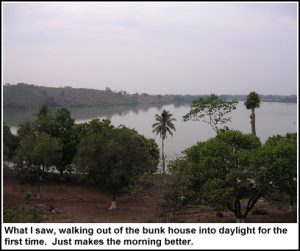

So there we were, sleeping away, safe in the knowledge we didn’t have to get up `til breakfast time, that we’d have a leisurely morning of light sightseeing, and that our flight didn’t leave until 1:45 that afternoon.

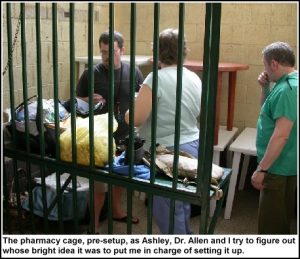

At 5:45 a.m. our hotel phone rang. It was Butch. He and Andrew had gotten up to see Flo off for her early flight and while they were up Butch had rechecked everyone’s flight information. It turned out that only Butch’s flight was scheduled to leave at 1:45 p.m. Everyone else’s flight was scheduled for 8:45 a.m., same as Flo’s. He said we had 15 minutes to pack all our stuff and be downstairs ready to go before Sylvana arrived with the van. He said he would call Tito and Jo Ann so they could bring us our empty luggage.

“Who was that?” Ashley asked as I put the phone down. I told her it was Butch and informed her of our predicament and deadline.

“You’re kidding me, right?” she said.

“Nope.”

To say that we were panicked by this news is putting it lightly. Neither of us had done any packing whatsoever the previous night and all our stuff was scattered. So there we were, neither of us even technically awake, running around the room grabbing clothing and possessions at random and hurling it all into bags unfolded. I’d been optimistic that we could get it all done in 15 minutes, but the whole still being mostly asleep part and the still being very fatigued from our week really put the crimp on that. It was like we couldn’t figure out what we were supposed to be doing next. And in addition to clothing, we had to pack up our fragile items too. Ash had four pieces of pottery and I had all the little clay sun-faces and several bags of plantain chips to worry about. We decided to put it all in our carry-on luggage, which we could at least be sure we would have on our persons and could be responsible for not breaking. We certainly didn’t trust the airlines to extend to us the same courtesy.

Through the haze of morning, it occurred to me that something else might be going on. What if this was all an elaborate practical joke on the part of Butch? I didn’t know how revenge-minded he was, but a prank of this magnitude would sufficiently get us back for all that stuff we did to him while he was sleeping last week. I could just see us breaking our butts packing and rushing downstairs only to find Butch there waiting with his camera to take our picture, laughing away at us. Ooh, that would be mean. We totally deserved it, but it would be mean. At that point, though, I figured having it be a prank was preferable to having to do a mad rush to the airport with Sylvana driving. She drove crazy enough when we weren’t under the gun, so I was not looking forward to the ride when we were.

After 10 minutes had passed, Butch called us back to tell us we could have until 6:15 to be downstairs. This was actually very good news, because we were nowhere near finished with packing. Unfortunately, it also meant that this was not likely a prank. And it wasn’t.

Perhaps ironically, the last time Ashley had been in Central America, she’d had to flee the country as fast as she could and here it looked like we were about to have to do the same all over again.

We got downstairs at 6:10. Jo Ann, Tito and Sylvana were there, ready to go, our luggage all packed in the back of Tito’s truck. We loaded up and hit the road. Fortunately, traffic in San Salvador isn’t very hectic at 6:15 on a Saturday morning. We were able to zip right along at a nice clip and made the 40 minute journey to the airport in seemingly record time.

San Salvador’s airport a very nice, but also very small for the number of travelers it sees. Even at 7a, it was extraordinarily crowded, and that was just outside. Once again, my airport fears set in and I became very paranoid about our luggage. I didn’t know if it was justified or not, but we’d not had any time for a San Sal airport expectations briefing. I’d have to just be paranoid and wing it.

We unloaded all the luggage from the truck outside the airport. Though most of it was empty, it was still an awful lot of luggage to be lugging around. Butch gave us money for the $32 exit fee we would have to pay and then Jo Ann and Sylvana helped us get everything inside while Tito stood guard at the car. The inside was even more crowded than the outside, with thick queues of people as far as the eye could see. We said our goodbyes to everyone and said we’d hope to see each other in a year. Then Dr. Allen, Mary Ann, Andrew, Flo, Ashley and I headed on in to our place in line.

Oddly, the huge lines didn’t seem to really hamper us much as far as getting through customs went. I paid the exit fee and was given receipts for all of us that we’d have to show at further gates. We then checked our luggage and proceeded to the next set of lines we’d have to stand in. With all the bustling of the crowd, we managed to get separated, which wasn’t a problem until it came time to show the receipts for our exit fees at the next set of doors. After that it was just a brief stop at the metal detectors, a quick x-ray of shoes and carryon luggage and we then found ourselves in the far less crowded airport terminal area. This was a very long hallway that lead to the boarding stations for all flights. Ours was pretty far down the hall, but we had a half hour to kill, so we weren’t in any great hurry.

We said our goodbyes to Flo, who was headed out on a separate flight to Honduras, and then ate breakfast at a small airport café where they served pastries and coffee.

Even with the big journey ahead of us, I was feeling surprisingly calm about it all. It’s like I knew that the worries of the world and the hustle and bustle didn’t really amount to anything and it would all work out okay. Why get stressed about it? I mentioned this to my traveling companions and they felt the same way.

Once aboard the plane, I put on my seatbelt as instructed. It was the first time a safety belt had graced my lap in all two weeks.

We could definitely tell we were back in the United States when we landed in Houston. It seemed like everyone we encountered was determined to be rude to us and the customs process suddenly became far more complex than it had been in Central America. Our passports and customs forms were checked repeatedly at every step and there was a lot more walking to do and many more long lines to stand in. Most of the customs people were cranky too, yet we remained strangely calm.

We went through the X-Ray machines and Dr. Allen’s otoscope turned up in the shot and he was pulled out of line so that all of his luggage could be inspected by hand. Never mind that four members of our five member party all had otoscopes in their bags too, his was the one to get flagged.

Once we arrived at our departure gate, everything was fine. Then the little sign that said “Charlotte” disappeared and one that said “Philadelphia” appeared in its place. Our gate had been moved. Most people would have been annoyed at this, but we just looked around and found the new one across the way and moved. No biggie.

While we waited at our new gate, a stewardess for Continental Airlines came by and gave us each claim tickets for our carry-on luggage. This was going to be another smaller plane, like the one we’d flown to Houston in from Charlotte, so there wouldn’t be space in the cabin for everyone’s carry-on bags. We took the forms, left our bags on the jet-way and didn’t think much about it.

We boarded at 1:20 for our 1:35 flight. Dr. Allen and Mary Ann had seats together as did Ashley and I. And Andrew was just across the aisle from us with a good view of the baggage handlers as they loaded everyone’s carryon luggage into the plane’s hold.

“Hey, that guy’s dropping bags!” Andrew said. We couldn’t see what was going on, but Andrew could and said the handler was just yanking bags off the jetway and letting them fall six feet to the ground. He held onto them as they fell to give them a guiding hand, but fall they did and seemed to be landing pretty hard. This was probably the first time we began to get really riled up for most of the trip. The whole point of putting fragile items in the carryons was so THIS wouldn’t happen and here it was anyway.

We called the plane’s steward over and told him what was going on. He said he’d file a report about it and that shut us up for the moment. Our nerves calmed again and we settled in. Soon they plane taxied out onto the runway to await clearance to take off.

And we waited.

And we waited.

And we waited.

At 1:40, the captain came on the speaker and told us that Charlotte was closed due to weather concerns and we’re going to have to wait 50 minutes before they would know if we’d be able to take off. At this point, the passengers around us began freaking out. People began grumbling, loudly and seemed to be of a mindset that asking us to wait for 50 whole minutes might just be the death of us, when it probably only meant the death of their connecting flights. Our party remained calm.

Somewhere near the front of the plane, a baby began screaming. Not crying, mind you, but screaming full-out, lungs ablaze, hardly stopping to take a breath. The air in the cabin, which had been warm from all the people aboard, now felt hot. Our party remained calm.

Two seats behind us, a man with a gruff British accent began loudly using his cell phone to call someone in Charlotte named Bonnie to tell her he would be coming in late. We know her name was Bonnie because he said her name, I’m gonna guess, at least 400 times during his brief call. “Bonnie? Bonnie? Can you hear me, Bonnie? Bonnie?” His connection was apparently not very good, so he just kept repeating her name, getting no response, hanging up and dialing again and repeating the previous process. Finally, after minutes of just going, “Bonnie?! Bonnie?! Bonnie?! Bonnie?!” he managed to get a good connection with her. “Bonnie?! … Bonnie, I can’t hear you…. I said, I CAN’T HEAR YOU!! … I hear loud voices in the background. … Bonnie?! Where are you at, Bonnie? Are you having trouble answering your phone, Bonnie?! I hear loud voices there, Bonnie … I said, I HEAR LOUD VOICES THERE, BONNIE!!!! … Can you go to some place where it isn’t so loud, Bonnie?!!”

This is what we all were hoping for by that point.

Evidently Bonnie relocated and he began asking her what the weather was like there, to which he didn’t seem to get a satisfactory response because he then began chastising her for not paying attention to the weather reports. If he had shut up for five seconds, he might have heard the three other people around us phone home to Charlotte to learn that the weather was very windy there.

Regardless of Bonnie’s bellowing British husband, we the mission party were still very calm about it all. Even Andrew, who had the most to lose since Charlotte was not his final destination and he had to make a connecting flight from there to D.C., didn’t seem at all put out by the delay.

We waited on the runway for 50 minutes, with the screaming baby and the screaming Mr. Bonnie going full blast.

At 2:30, the flight crew came on the speakers and announced that we still didn’t know our take off time, but were going to head back to the terminal anyway because a passenger needed to get off the plane. I assumed the guy was maybe just connecting in Charlotte too and wanted to get off and try and catch a more direct flight to his destination. So they fired up the engine and we taxied back within walking distance of one of the airport terminals, but they didn’t let us off. Instead, we just sat there waiting, as the flight crew explained, for a bus to come and drive us to the terminal.

After at least 10 minutes, the steward came back on the speaker and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, we were taxiing to a gate to allow a passenger off who was sick. But now the passenger doesn’t want off, so I’m not sure what we’re doing here.”

We all laughed at that. I had to hand it to the flight crew for having personality. Shortly after this, they came back on and announced that we had received word from Charlotte and would be taking off at 22 past the hour. Since it was now around 2:50, both we and the captain had assumed Charlotte meant 3:22. Uh, no. It turns out they meant 4:22, a fact that we didn’t learn until we’d waited ten more minutes. The captain had to come on and break the news to us that it would be another hour and 20 minutes before we could leave.

“If you want to deplane, we’ll call some more buses and they’ll probably take another hour,” he then said.

The passengers voted to deplane. This time the buses came fairly fast and we were whisked the 100 grueling yards to the terminal. Once there, we were told we would only have 15 minutes in the terminal before we had to bus up and head back to the plane, so we needed to be sure to stay near the announcement system speakers so we would know when to get back on the busses.

So we sat around in the terminal for 15 minutes. Far from being annoyed, I think most of our party found the whole thing pretty funny by this point. We found it even more funny when we bused back to the plane and it was discovered that Mr. Bonnie had missed the bus ride and was not aboard. The steward walked to the man’s seat and asked if anyone knew who the man was and where he was. This inquiry was answered by a chorus of other passengers saying, “Bonnie? Bonnie? Bonnie?”

The captain gives Mr. Bonnie two minutes to appear, then shut the door to the plane. Ten minutes later, Mr. Bonnie came running across the tarmac and, astroundingly, they let him in. He returned to his seat, quite shame faced.

At 4:22, we took off.

Our flight home was beautiful with an amazing view of the sun as it set in the west.

Our arrival in Charlotte was indeed accompanied by some bumpy weather, though. It was pretty windy then, so if it had been windier earlier I’m glad they kept us on the ground for as long as they did. I don’t take too well to having my plane tossed around in the air. The pilots got us down just fine, though.

We went through our carry-on bags once they were returned to us at the jet-way. Nothing seemed to be broken at first glance, but when we went back through them the following day we did find that part of Ash’s clay cooking set had been broken and a couple of the clay sun-faces I had were chipped. We also learned from the Continental Airlines website that their basic policy on this is that even if it IS their fault it’s not their fault, they take no responsibility and they won’t be reimbursing anyone for any items that they damaged. Thanks Continental.

By the time of our late arrival, Andrew had indeed missed his flight. But he was able to make arrangements to pick up a flight the following morning and could come stay with us at Ma & Pa’s back in Hildebran and drive over in the morning.

In a reverse of our first day at the airport, we shuttle bused with our luggage back to Dr. Allen’s truck. I was even wearing the same clothes, and pulled my hoodie/pillow out of my bag to keep me warm against the North Carolina chill. I had hoped the bus driver who’d marveled at all the bags we had two weeks ago would be our driver, but it wasn’t him.

We were all quite hungry, by then, so we stopped off at a Ryans buffet in Gastonia on the way home, where I had a great deal of difficulty not saying “gracias” to our waitress whenever she refilled my tea. It was fantastic food, but I ate far too much of it—stuffed myself stupid, really—and then was embarrassed that I’d eaten so much when I’d just returned from a place where people often have so little. I was miserable in mind and body for the rest of the evening.

Arriving home at Ma & Pa’s house was bittersweet. On the one hand, I was glad it still was Ma AND Pa’s house because Pa had lived through his fall from the roof of the cabin he’s building nearby. On the other hand, it was tough for Ashley to see her father sitting there encased in neck and wrist braces. Seeing him like that reminded her that we’d nearly lost him. She put on a good show when in his presence, but that night was a fairly sleepless one for her.

Pa was doing well. He was still on some pretty serious pain medication, but his wrist was already doing better than expected. He knew then that his recovery was going to be a long one, but his determination to get back up and running and his perseverance at physical therapy have gone a long way toward making that recovery faster. We didn’t know it then, but Pa would remain in the neck brace until mid-June, but his wrist has made a far better recovery than his doctors ever thought. It may never be 100 percent again, but it won’t be because Pa didn’t try to get it there.

We sat in the living room that night, with Dr. Allen, Mary Ann and Andrew, telling Ma & Pa some of the highlights of our trip. It was very hard to do, because at that point everything we’d experienced felt far too big to even know where to begin. You can’t encapsulate an experience like that in an evening (or even in a blog over the course of several months—believe me, I tried and it just hasn’t worked to my liking).

As we were to learn over the coming days, most of the time you don’t even have an evening’s worth of time to spare to tell folks about your journey; instead you have to give people who ask about it a quick snapshot in just a few minutes. Ashley’s method was to simply explain that we saw over 2600 patients in two countries and over 850 of them were lead to Christ. That seems to work pretty well.

THE END (FOR NOW)

DATELINE: Friday, April 1, 2005

Our final clinic day wasn’t originally supposed to occur on Friday at all. Our original schedule called for us to have Friday off so we could go out and see the sights in San Salvador. However, since we didn’t arrive in the country until Monday, which nixed the planned Monday clinic, and since we still had plenty of meds in the pharmacy, we decided to go ahead and do a clinic on Friday. Tito and Jo Ann suggested we do a half-day clinic so that we could still have time for some sight-seeing, so we agreed to do that.

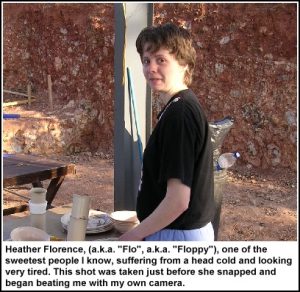

On the way to the clinic, Butch asked Flo if she would be comfortable giving her testimony to the crowd of patients that morning. Flo didn’t seem sure if she wanted to do this at first, and I could feel Butch’s eyes scanning the rest of us for any takers already. The trouble was, I could have given my testimony, but it’s not exactly an awe-inspiring one. It’s pretty run of the mill, in fact.

I first became a Christian a fairly early age. Though I grew up Southern Baptist, my father was something of a religious free-spirit (well, a religious free-spirit with pretty firmly held views as to how things work from a religious standpoint) who wasn’t afraid to try out the services of different denominations or even altogether different faiths. I’ve been to Greek Orthodox services, Synagogues, Catholic Mass, Mennonite services, Holy Rollin’ Speakin’ in Tongues Pentecostal services, plus just about any variation on Protestant services you’d care to name. I mostly hated it as a kid. There we’d be, driving across country when suddenly dad would get it in his head that we had to go hang out with the Quakers for the evening, and off my sister and I would be whisked to some strange little back-road church where they didn’t do things like we were used to. As an adult, I’m really glad to have had all those experiences and have thanked my dad for taking me to so many different churches. Still hated it at the time.

Even with that background, it wasn’t until the age of 8 that things first started to congeal in my head as to where I fit into religion and spirituality. It was while attending a three day church camp based at a local community college near the Mississippi town in which I grew up that things started to make sense. This was my first time being away from home by myself, so it was kind of a big step for me. But my best friend Scott Long was there, so that’s where I wanted to be.

In addition to all the usual fun camp-activities, (including a talent show at which I came in 2nd and Scott came in 1st), we were also given Bible lessons throughout the day as well as hearing youth-tailored sermons from our camp minister. We also memorized Bible verses. The first of the two main ones I remember was, of course, John 3:16, “For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son that whosoever believeth in him shall not perish but have everlasting life.” This is perhaps the greatest verse in the whole Bible, for it contains the key to salvation. It’s got the whole Wages of Sin is Death thing built in, but it shows you the way out at the same time. But the real Rosetta Stone for John 3:16, for me, was the other verse I memorized, Romans 3:23, “For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” The camp minister explained that this meant that human beings are born sinners and there’s not a one of us who can live up to the commandments and laws God laid down in the Old Testament. (You know, all those rules and regs that the Jews of the day spent much of their time sacrificing things to gain forgiveness for breaking.) This was why Jesus sacrifice on the cross was so necessary. He, an innocent man, died a horrible death, the death of a criminal/sinner, so that we would not have to make blood sacrifices in order to atone for our sinful nature.

Hearing that verse and having its meaning explained to me was a profound moment for me. I can still see the inside of that meeting hall on that community college campus like a snapshot in my head of the moment the meaning hit me. The verse means, we’re all sinners, humanity as a whole with me included. No one is exempt, cause that’s the definition of ALL. Suddenly this nebulous concept of all these nameless sinners getting sent to hell for sinning, that everyone had been talking about, hit close to home. I realized, perhaps for the first time, that I too was a sinner. Sure, I wasn’t sinning big time or anything—I mean, I hadn’t knocked over a liquor store or killed anybody—but I couldn’t say I was even living up to the rest of the 10 Commandments to the best of my ability, let alone the myriad of other things a person could chose to do (or not do) that constituted sin. (Sin, after all, is defined best as disobedience to God.)

Ah, but then my little mind headed back to John 3:16 territory, particularly the bit about “whosoever believeth in him shall not perish but have everlasting life.” Hey, there ya go! I believed in God, I believed in Jesus, so therefore in my mind, I was saved. It was an amazing thing. I felt all tingly inside at the thought of it and figured that’s what happened to a person when they got saved—they felt all tingly.

I came home from camp and announced to my dad that I was saved.

“You are?” he asked, a bit hesitantly. So I told him about Romans 3:23 and my realization over its meaning and its correlation to John 3:16. I didn’t use words like realization and correlation, but you get the gist. Dad listened and then told me that my revelations on those verses were good, but he didn’t think I’d quite hit the mark. I wasn’t saved yet.

Dad let me stew on that one for a while and stew I did.

Within a day or two, though, it began to really bother me. How could I not be saved? I’d felt all tingly and everything, like something had changed within me. Then, in true Michael Binkley style, (that’s a Bloom County reference, folks—pay attention), I woke my dad up in the middle of the night and asked him how I could become a Christian. Dad groggily realized I was serious and he woke up enough to explain a few basics to me.

Dad told me that the way to become a Christian is that first you must admit to God that you are a sinner. It’s not enough just to realize that you’re a sinner, you must actually admit it to God. You must also ask him to forgive you of those sins. Next you must acknowledge that you believe Jesus was God’s son and that he died on the cross in our place as the ultimate sacrifice so that we didn’t have to endure the punishment of hell. And finally you must ask Jesus to grant you the grace of his Salvation and accept you into his eternal kingdom. With Dad’s help, I prayed that prayer.

This is not to say it’s been all smooth sailing since. Not by a stretch. And it wasn’t the last time I would pray that prayer. See, as a child I was always a worrier. I used to spend a lot of time fretting that somehow I’d said the salvation prayer wrong the first time and wasn’t really a Christian. No one wants to go to hell on a technicality, so I prayed it again and again over the years. My father finally pointed out to me that most people who aren’t Christians don’t worry over their salvation or lack thereof so much and it’s usually the people who are already Christians that spend so much time worrying about their sinfulness and seeking redemption. Made sense.

I also have to admit to falling by the wayside with my faith quite a bit over my life. I felt pretty strong in it when I was a kid all the way up through high school. I had my ups and downs, but I felt like I was on the path. During college, my downs became more frequent, but I had good friends who were Christians who helped keep me on the path most of the time. After college, though, I spent several years away from church altogether–not out of any philosophical differences, per se, but mostly because I was unwilling to upset my comfortable life of not going to church by actually getting off my duff and going there only to be reminded of how much I was disobeying God in the first place.

These days, thanks in large part to my wife’s influence, I’m a regular church-goer. Not that that in and of itself means anything, because I’m probably just as big a sinner as I was before in many regards. But I have a good church and good friends in it who go a long way toward helping me stick to the path and grow in my relationship with God. And that is the ultimate goal that many people miss.

There’s a common misconception that Christianity is all about Do’s and Don’ts. And many Christians get wound up in the whole “don’ts” part, as though actions are somehow what saves in the first place. They don’t. At its core Christianity is supposed to be about an ongoing relationship between you and Jesus, one where you allow him to steer your life where He would have it go and you’re along for the ride, putting your faith in him that He will bring you through the experience. I’m thankful to say that I’ve had quite a few Step out on Faith moments in my life, this trip being a big one of them. God has always brought me through. Do I allow him to steer my life at all times. Unfortunately, no. And that’s part of the ongoing relationship–learning to relinquish.

So my testimony is pretty normal. Not that it would have been a bad one to give, being as how the vast majority of people who become Christians probably have fairly normal testimonies to give. As it stood, though, I didn’t have to give mine during our clinic that day. Flo went ahead and gave hers that morning and I was left wondering what I might have said.

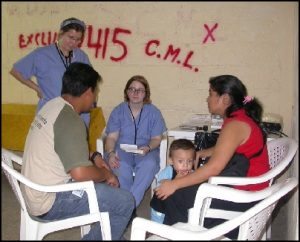

Only 65 patient numbers were given out Friday morning, but we let some more in after we saw that there were some people truly in need who arrived too late to get numbers. One lady who arrived late complained to us that she had not heard our clinic was even in the area until that very morning. We wound up seeing her anyway.

I know this number system for seeing patients seems cold and clinical, but it’s almost the only way to run things. Dr. Allen remarked through both weeks of this mission that he had never seen such smooth and seemingly practiced organization outside of mission work. Such things certainly don’t happen so spontaneously back in the states. We knew, though, that this was not practiced because this was indeed the Word of Life El Salvador Team’s fist such medical mission.

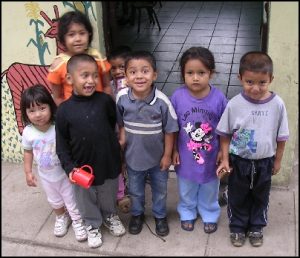

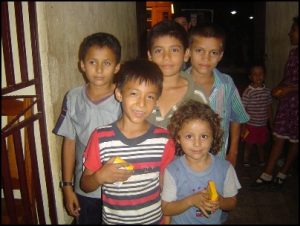

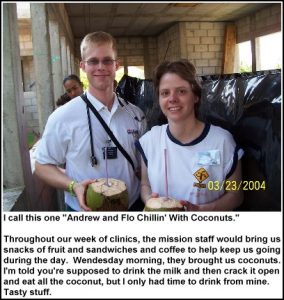

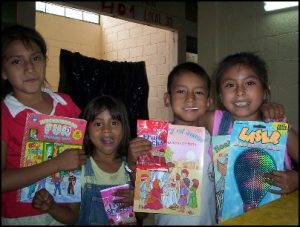

Because we had so many meds left, much of it in vitamin form, all prescriptions Friday got vitamins whether they wanted them or not and usually a two month supply. We also discovered that we still had loads and loads of candy, so I began bagging up fistfuls of it into our ziplock prescription bags and kept it in a box by the pharmacy window to dispense to any children who happened by with their parents.

In the morning, I spied a little girl out front who didn’t seem to be having such a great time, so I went out with a bottle of bubble stuff and blew bubbles for her to demonstrate how it was done, then gave her the bottle. She smiled and began blowing bubbles and soon had friends gathered round. A few minutes later, I looked out again to see one of her older friends running around with the girl’s bubble stuff. At first I was mad that this older girl might have taken the bubble stuff away from the younger one. Then I figured out that they were all just sharing. I grabbed a couple more bottles and went out to give to the girl and some of the other kids out there. Soon bubbles were floating freely throughout the clinic.

Not too long later, I had a little more time off and went out to juggle for the kids. I’d been saving my juggling balls for most of the trip and had brought quite a few. Most of them were from my personal juggling materials collection, many of them just rubber balls and raquet balls, the very ones I’d used when I first learned to juggle. I don’t use them anymore, preferring to use juggling bags when I juggle at all, so I figured relocating these to Central America would be a good thing. After I’d juggled two balls with one hand and three balls with two hands for a bit, I threw the balls to the three nearest kids and nodded that they should keep them. (You can communicate so much with a nod, at least in my mind.) They dashed off to play with their new toys. Soon after I returned to work, I began to notice children gathered at the pharmacy door. Word had spread I was giving out toys and the kids were looking awfully hopeful. After letting them stare in at me for a while, I did another juggling routine and then passed the balls out to the gathered kids. They disappeared and were replaced with new kids. So then I gave out the remaining balls I had and more kids arrived. Then I gave away all the rest of the bubble stuff and more kids arrived. Finally, I handed out some of our prescription bags full of candy to the remaining kids and that seemed to do the trick. They grinned and dashed away.

In addition to giving out extra meds for diagnosed problems, the docs on Friday also began prescribing some placebo meds as well.

Placebos, for those who don’t know, are medicines or harmless substitutes for medicines given to patients in place of real medicines. These days, they’re mostly used for control groups in pharmaceutical testing labs, but in the old days doctors prescribed placebos all the time when they suspected a patient’s ailment was mostly in their head.

In our clinic, we weren’t exactly using them in either manner, but instead used them in cases where we could not medically treat the symptoms described. I’ve said it before here, but it stands repeating: Doctors can attest that medicine is often more art than science. If a patient can be sold on the idea that something is going to make them better or will cause a condition to stop, they will very often get better or the condition will stop.

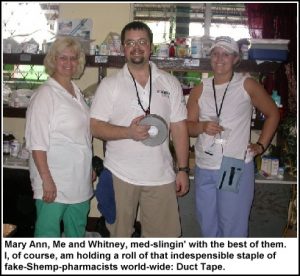

Dr. Allen said that this sort of practice used to happen all the time in doctor’s offices across the U.S. And pharmacists, back in the day, were used to seeing prescriptions for a veritable wonder drug called Obecalp, (that’s placebo spelled backwards), that was used to treat a huge variety of conditions. However, in the intervening years, medicine has become a whole lot more regulated, so these days doctors in the states pretty much have to put up with their hypochondriac patients.

The placebo meds we gave out were genuine meds, like Benadryl and Chlortrimeton, but they were prescribed for conditions those drugs were not intended to treat. Throughout the morning, we in the pharmacy would get prescriptions for Benadryl and beside the drug-name on the prescription would be a little note from Dr. Allen explaining what condition this drug was being prescribed for, so if a patient asked if it was for his nerves or for his insomnia we could say, “Yes, that’s what it’s being prescribed for.”

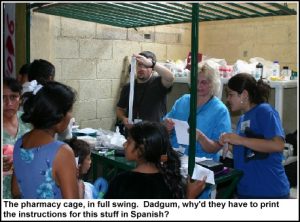

While dispensing meds Friday morning, one of our patients surprised me. Though I had Claudia there as a translator, I gave the lady instructions in Spanish since the instructions were simple.

“Tres diarias. En la manana, en la tarde, en la noche.”

“So, it’s one pill three times per day?” the lady replied in perfect English. I was dumbstruck at first, then grinned at the patient.

“You speak English,” I said.

“Yes,” she said.

So I explained the rest of her prescriptions in English and finished up with “God be with you” instead of my usual “Dios te bendiga.”

Claudia asked me about my Spanish skills. I had to admit that to call them skills was really pushing the definition of the word. Sure, I’d taken over six semesters of it in college, but technically what I’d really done is take 6 semesters of a 4 semester course. I took Spanish I, enjoyed it, did fairly well in it, and then promptly sat out of it for an entire year before taking Spanish II. Naturally, I had forgotten so much of my knowledge from Spanish I that I began failing II miserably and had to drop it. So I came back for round 2 the next semester, having not so much as cracked my Spanish I book for a brush up, and proceeded to fail the class yet again and was forced to drop it. After this, I decided to audit Spanish I and really do the refresher course right. That helped tremendously and I proceeded through Spanish II, III and IV. I can’t say I got through them with no troubles, but I got through them.

I found, however, that throughout my two weeks in Central America, much of my Spanish skills had returned to me, far more than I had expected. Verb forms that I’d forgotten were reconnecting in my head and little bits of things would filter out every now and then.

“Hey, I remember Tener!” I said, just after a patient asked me if I was the guy who had the patient numbers. I didn’t know what to tell her so I directed her to someone else. Then I realized, I could have just said, “No tengo numeros” or “I have no numbers” and answered her question.

Toward the end of our clinic day, some kids from the neighborhood came up and asked if we were seeing any more patients. The missionary staff member whose job it had been to give out numbers explained that we weren’t and that we were sorry. The kids left. On their way down the street, they happened to pass by Butch, who was coming back from the store with more goodies. He noticed that one of the kids was barefooted and limping and was bleeding from his toe. Butch got the kid’s attention and helped him back to the clinic where he was put right into the system. Turned out his injured toe was in pretty bad shape and in danger of going septic on him. It was providence that Butch happened by at that moment and noticed it. Kid would have been bad off otherwise.

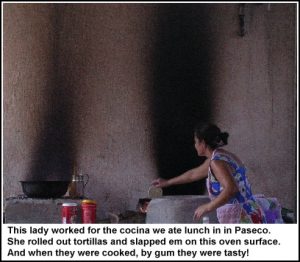

At 1:30 p we saw our last patient, filled our last prescription and then went next door to our final clinic lunch. I savored the home made potato chips one last time. We all feasted and had extra sandwiches afterwards and enjoyed the company.

After lunch, we packed up the clinic. Even giving out as much extra meds as we had earlier, the pharmacy still had quite a lot of medication left over. We packed as much of it into the plastic tubs as we could and the rest into the remaining suitcases. We would be leaving it in the care of Tito and Jo Ann for use with future missions or to distribute to those in need as they saw fit.

When the clinic was packed away, Butch wanted to get a group photo with everyone. Unfortunately, he chose to take this photo beneath the cicada tree. He asked Dr. Allen and I to take up positions as the end markers for the photo and then once we were positioned he asked everyone else to file in between us. There we stood, beneath the cicada tree while Butch got us into position, the cicada urine literally raining down upon our heads. It was so very very foul. Fortunately, I remembered that Ashley had made me pack a disposable plastic rain poncho, so I pulled it out of my backpack and put it on. After much jostling, we were finally in place and Butch snapped several photos before we revolted and dashed out from under the tree.

When the clinic was packed away, Butch wanted to get a group photo with everyone. Unfortunately, he chose to take this photo beneath the cicada tree. He asked Dr. Allen and I to take up positions as the end markers for the photo and then once we were positioned he asked everyone else to file in between us. There we stood, beneath the cicada tree while Butch got us into position, the cicada urine literally raining down upon our heads. It was so very very foul. Fortunately, I remembered that Ashley had made me pack a disposable plastic rain poncho, so I pulled it out of my backpack and put it on. After much jostling, we were finally in place and Butch snapped several photos before we revolted and dashed out from under the tree.

I will not miss those bugs.

We drove back to the hotel to freshen up and rest a bit before heading out to see the sights of San Salvador. The plan was to souvenir shop for a while, then go out to dinner with much of the mission staff around 7.

We headed first to an Indian Market to shop for souvenirs. There were enough translators to go around, but mostly the shopkeepers were used to dealing with Americans so it wasn’t always a necessity. I found some really nice gifts to take back home. Once again the American dollar goes a long way, and where it didn’t there was always the opportunity to haggle. Ashley found some really nice pottery, including a colorful chip dish with salsa bowl and a clay ware set that included a large urn in which you could put a Sterno to cook through a smaller pot that rested on top. It was sort of like a fondue pot, without the long forks.

We headed first to an Indian Market to shop for souvenirs. There were enough translators to go around, but mostly the shopkeepers were used to dealing with Americans so it wasn’t always a necessity. I found some really nice gifts to take back home. Once again the American dollar goes a long way, and where it didn’t there was always the opportunity to haggle. Ashley found some really nice pottery, including a colorful chip dish with salsa bowl and a clay ware set that included a large urn in which you could put a Sterno to cook through a smaller pot that rested on top. It was sort of like a fondue pot, without the long forks.

After shopping there, we still had a bit of time before our reservations at the restaurant, so Jo Ann and Sylvana took us to a very swanky supermarket. I had mentioned to Jo Ann that I wanted to visit a supermarket at some point because I was looking to buy some instant soup for my boss. My boss’s sister-in-law is Guatemalan and she introduced my boss to a Knor-brand instant soup from Guatemala that was terribly delicious. My boss wanted me to score some if I could. I never got the chance to grocery shop in Guatemala, though, but figured El Salvador would probably have the same sorts of things. Meanwhile, Ashley wanted to shop for some fried plantains and Fresca. So we all followed Jo Ann to a grocery store located in a high-end strip-mall full of expensive shops. Our translators told us as we arrived that this was where the wealthy people of San Salvador came to shop. True enough, the place was surrounded by a very Yuppie-like crowd, out for their Friday evening.

Once inside, we located the soup aisle, but while they had plenty of Knor soups, they didn’t have the particular flavor I was looking for. I loaded up on them all the same since they were only a quarter each. We also found some individual bags of fried plantains to take back with us to give as souvenirs as well as some El Salvadorian coffee and Fresca.

While we were still browsing the chip aisle, one of the missionaries, Nestor, looked down into our basket and said, “You are buying whiskey?”

“No, no,” Ashley said, thinking he was joking around. “We’re only buying soup and chips.”

Nestor pointed into our basket again, where there indeed was a bottle of tequila in the bottom.

“I’ve been framed!” I said, looking around to see if the culprit was near. Not that I eschew alcohol by any means. I’m a beer-drinkin’ Baptist, after all, and do not hold with the oft-held belief that drinking alcohol is a sin. (I believe Jesus drank enough wine during his time on earth to prove my point.) However, even with that in mind, we weren’t really looking to buy any alcohol then. It took some time and guesswork to figure out who stashed the tequila. Naturally, Butch was our number one suspect, but it was Flo who figured out that it was really Sylvana who had stashed the booze in our basket. When confronted, Sylvana laughed and laughed.

We were to get another shock when we went to pay for our purchases. After the cashier rang up everything, the total price according to the register screen, was like 170.50. Fortunately, Nestor was there to aid us in translation and explained that the 170.50 was in the old El Salvadorian currency, back before the economy switched to American dollars, so we really owed around $15.

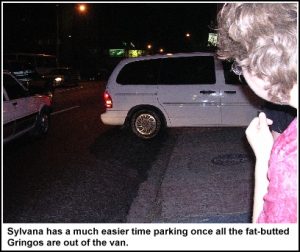

Next we climbed back into Sylvana’s van and rode to the restaurant of our dinner reservation at the Hunan Chinese Restaurant. (I know, I know, we came all the way to El Salvador to eat Chinese food. Shut up.) Sylvana, of course, was driving like a mad woman and that extended itself to parking. The restaurant was in a multi-story office building that we later saw consisted mostly of doctors offices and the like. However, we approached the building from the far two lanes of a very busy four lane road and in order to park we would have to cut across the two lanes of oncoming traffic. Sylvana waited and waited until we had just enough time to squeeze through a gap in the traffic and then she started to gun it before coming to a screeching halt in the middle of the lanes.

What we didn’t realize until then was that the road itself, through paving and repaving, was now quite a bit higher than the parking area in front of the building. In order to park, the van would have to drive down the rolling dip of the edge of the asphalt and then onto the rise of the concrete sloped parking space. With all eight of us in the van, however, this was an impossibility without gouging out the bottom of the van in the process.

What we didn’t realize until then was that the road itself, through paving and repaving, was now quite a bit higher than the parking area in front of the building. In order to park, the van would have to drive down the rolling dip of the edge of the asphalt and then onto the rise of the concrete sloped parking space. With all eight of us in the van, however, this was an impossibility without gouging out the bottom of the van in the process.

“Uh oh,” Sylvana said.

“We have to get out?” Flo asked.

“Yes.”

So there we were, pouring out of the van like a Chinese fire-drill (ironically enough), two lanes of honking cars beaming their headlights at us as we scrambled to get out of the road. Our weight no longer a factor, Sylvana gingerly pulled into the parking space and we were set.

Dinner was fantastic and the restaurant quite nice. In fact, I hadn’t realized it was going to be that nice when I’d dressed for the evening.

“I’m glad I wore my best dirty T-shirt and flip flops,” I told Ashley. I didn’t have much of a choice, though. If it wasn’t a T-shirt and shorts it would have been the world’s wrinkliest dress-shirt and pair of corduroys, since my dressier clothes had spent the past two weeks wadded in my luggage.

Inside, we met up with many other members of the mission staff and were seated around an enormous round table that seated 16 people. Soon we had hot tea and shark fin soup to sample while our choice of dishes was prepared. When the food arrived, they came on big platters that were placed on the giant Lazy Susan in the middle of the table, and we took turns spinning it and sampling from a variety of great food.

After dinner, Jo Ann told us that Tito wanted to say a few words to us.

Though Tito is the leader of the Word of Life mission in El Salvador, we’d heard very little from him all week long. We’d been told in advance that he was a quiet man, but a very good soul and he had proved to be that throughout the week. I think we all assumed when Jo Ann said Tito would like to say a few words to us, that he would say a few words in Spanish and that she would translate them into English for us. However, what happened next surprised us all. Tito began speaking English—very good English. And he spoke in very good English for ten minutes straight. When he was finished, all we could do was grin and congratulate him on having fooled us all week. He’d never said he couldn’t speak English, but we’d all assumed as much from his quiet demeanor.

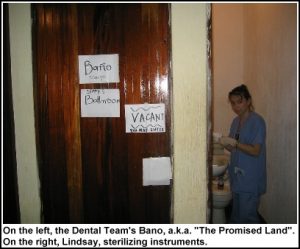

After dinner, we said our goodbyes to most of the mission staff and headed back to Tito and Jo Ann’s house to deal with the luggage. All of our clinic supplies had been brought back to their home following our day and it was time to divide it up and see how we were getting things back to the states. The meds and remaining toys and candy we left behind for future missions or as Tito and Jo Ann saw fit to distribute. There were a few other sundry supplies and items of donated clothing that we left as well. This left a lot of empty luggage, which we treated like Russian nesting dolls, putting bags within bags within bags to consolidate space. We also made plans for breakfast the following morning. Jo Ann knew of a place that sold an El Salvadoran dish called a pupusa which was supposed to be a great breakfast food. The place also sold genuine fried plantains, which is what I wanted. The only member of our team who wouldn’t be able to go was Flo and this was because she had an early flight out at 8:45 the next morning to go to Honduras, where she would be staying with some friends she had from previous mission trips. She’d have to leave the hotel around 6 a.m.

We left all the empty luggage with Jo Ann and Tito and headed back to the hotel in the van. Ash and I got to sleep around 11:30, savoring the knowledge that we’d get to sleep in a bit in the morning, go have a fabulous breakfast, pack up our stuff and be ready to go by our 1:45 p.m. flight back home.

DATELINE: Thursday, March 31, 2005

Since we didn’t leave the clinic until after 9 and didn’t eat supper until after 10 and didn’t get back to our hotel rooms until nearly 11, we didn’t get much sleep until nearly midnight. When the alarm went off at nearly 7, Ashley and I were in no mood to actually get up. We’d both been worked to a frazzle the day before and had very little sleep in between, so we just could barely face getting up at all. I don’t know how we managed not to growl any more at one another than we did, but we arose and got showered and dressed with very little griping.

None of the rest of Team Gringo were especially bright or chipper, but I don’t think any of us dreaded the day itself. We just wished we had more energy to give to it. As for me, though, I needed not only more energy but also a better attitude. I was a right cranky man, for no real reason, and it seemed like everything was irritating me. That attitude, unfortunately followed me all the way to the clinic site.

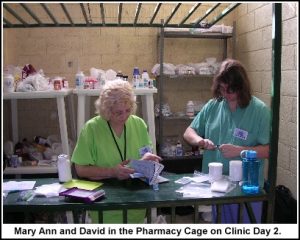

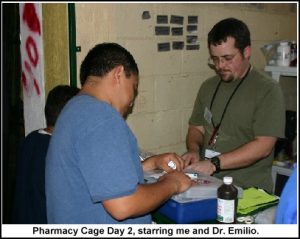

In the pharmacy, we had a little down time before patients began showing up so we bagged more and more medicine. We could hardly keep up with the demand for vitamins the day before, so that was a primary goal for pre-bagging. For much of the day, whenever any of us had a spare moment, we bagged vitamins. Unfortunately, it was difficult for any of us to do this without taking up valuable counter space and generally getting in the way. And you could only bag meds for so long before the swell of patients with prescriptions called you away to help with the filling, leaving a mess behind from the stuff you were bagging before, clogging the counters and other spaces. I began to get growly—never a good sign.

We also bagged a bunch of other meds, trying to stick to the doc’s new favorite dispensing amount of 30 pills, instead of 20, only this time to have prescription after prescription arrive in amounts of 20!!!

“Porque? Porque? Porque?!!!!”

I also began to become further irritated with my fellow pharmacy staffers, particularly Mary Ann, who kept insisting on doing everything the correct way instead of the semi-half-assed method I preferred. (I fully admit to being wrong here.) I can’t even recall the exact details of what I was irritated about, except to say that it was over a medicine, probably Amoxil, that we had to instruct the patients how to pre-mix, but the way I wanted to do it required them to put 2 ml less water into the powered Amoxil than the dose actually called for. I think this was because we’d run out of the syringes that were easy to mark, or maybe we’d run out of our 250 mg Amoxil and were having to recalculate doses from the 400 mg Amoxil we had plenty of. I don’t recall. What I do recall is that Mary Ann insisted, as well she should have, on getting the dose exactly right, instead of having a dose with slightly less water in it, as I was trying to do. This was probably the pinnacle of my ire for the day, but even as I was fuming inwardly and sometimes outwardly about it, I realized that Mary Ann was only trying to do the right thing for the patient, and that no matter how little the differences in out methods might actually matter, I should defer to her experience in these things, especially considering that I’M NOT A MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL and SHE IS.

After that realization, my attitude became quite a bit better. It often takes embarrassing myself with my own bad-behavior for me to recognize how badly I’m behaving and make the necessary adjustments to stop it.

One of the major patient pharmaceutical requests was insect repellant. In a country with the kind of large and aggressive bugs that this one seemed to have, it stood to reason. However, the pharmacy did not stock bug dope of any kind. In some cases, however, there were children patients who had enough bug bites on them that it seemed like some sort of repellent would be good to prescribe. This is when Ashley had the idea of concocting a 1 percent solution of Deet in water. Deet is one of the most powerful insect repellents on the planet. Unfortunately, it is also quite dangerous when it comes to killing off brain cells in children and is not recommended for use with children. Her idea was to create a very weak solution of it to use on the child’s skin to ward off bity bugs. I let her mix it, so as not to screw it up and put too much in it myself. But I didn’t feel good about it. Most of the meds we had in house wouldn’t kill a person if they took too much. And even though the Deet solution was given out in a child-proof bottle that I’d drawn a skull and crossbones on, I didn’t feel safe that the kid we’d prescribe it for wouldn’t find a way to open it and drink the stuff. Later in the day, Ash prescribed another bottle of it, which I mixed up and labeled, but then went to her and let her know that I didn’t feel good about giving such poison out. We wound up nixing it from the prescription.

We did do some far safer mixing when it came to creative prescriptions. Because we were seeing so many skin rashes, the docs had been prescribing lots of hydro-cortisone cream. So much that we ran out of it pretty early in the day. Dr. Allen suggested that we make our own cream solution by mixing 1 part Triamcinilone Cream (a far more powerful skin ointment than Hydro-cortisone) with 4 parts hand lotion. We mixed it up in tiny little baggies, labeled it as to what was in it and in what ratio and then gave it out as prescribed. I wound up mixing quite a few of these throughout the day.

Dr. Grace was back with us for most of the day on Thursday, so we kept a pretty steady patient rate.

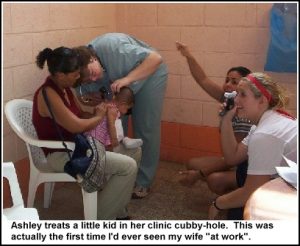

On Thursday, Ashley had to leave for her first house-call. A woman had come to the clinic and explained that her son had suffered a severe burn to his leg and was unable to walk to the clinic for treatment. So Ashley, Butch and a translator took some supplies and some meds from the pharmacy that would be good for treating burns and headed out by vehicle with the mother to visit her home. Ash told me later that she didn’t know what to expect. For all she knew, the boy had just burned himself horribly that morning and she didn’t have the know how to do much, other than tell his parents they needed to get him to a hospital. Or if the burn had happened some time ago, she would likely have to deal with improper bandaging and infection. She prayed that God would give her insight.

They drove for a couple of miles until they were in a wooded area where they came upon a house. The boy himself was seated on the front porch of the house waiting. The boy was wearing long trousers and didn’t seem to be in any obvious pain. Ashley, through the translator, asked if she could see his burn and he lifted up one of the legs of his trousers, which had been split along the side for easy access. The leg had what looked like a fairly fresh dressing on it. The boy removed the bandages for her to let her see the burn itself. Upon seeing it, Ashley was confused, because she couldn’t figure out why the burn had a crosshatched pattern. It was also not in nearly as bad condition as she was expecting. Then she realized why it had the crosshatched pattern. The boy had received skin grafts on the burn already. This burn had been treated by physicians who had shaved skin from elsewhere on his body and applied it to the burned leg, to help grow new tissue there. The reason for the crosshatched pattern is that skin heals far better from lots of smaller wounds rather than one large wound. So before the shaved skin is applied it is first cut into a latticework-like pattern that facilitates faster healing. Not all of the skin graft had taken, so there were burn patches showing through, but Ashley said the whole thing seemed to be healing fairly well. Since she was there, Ashley applied a burn bandage infused with silver which would help in the healing process.

In the afternoon, we were brought more nifty snacks purchased at a local neighborhood store. Butch returned from the store bearing a large roll of snack bags, the kind chips usually come in. I say they were in a roll and what I mean by this is that instead of individual bags of chips, these bags were still attached to one another, as though they’d missed a key process at the packaging plant in which they were to have been cut apart. At a mere 5 cents American per bag, though, these rolls of chips were actually a pretty neat idea. After all, it’s much easier to transport a long coil of chips than 20 mini bags. Butch had also bought three different varieties so we could each get a good sample of the kind of snack junk-food El Salvador had to offer.

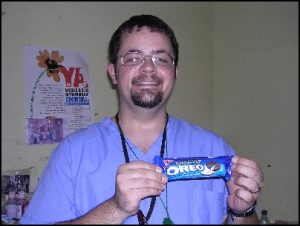

One of the varieties was basically Cheetos. They weren’t called Cheetos, but that’s what they were. And unlike my experience with El Salvadorian Oreos, these Cheetos actually tasted like real Cheetos. In fact, they were almost better than real Cheetos. Almost.

The next variety were a kind of bacon flavored puffed snack that had a similar texture to Funyuns. They were quite tasty. We don’t really have an equivalent in this country, so next time you’re in Central America you should pick up a bag of them. Sorry, I don’t recall the brand name.

The last variety was my favorite, though. They were salted and deep fried plantain chips. Yesiree, these were the best of the bunch. They were sweet and salty and crunchy all at the same time. Just Mwah! Goodness! I ate two bags of them without breaking a sweat.

“You know, fried plantains are a breakfast food here,” Jo Ann said. She didn’t mean the fried plantain chips, but actual plantains deep fried and coated with powdered sugar. I suddenly found I had a hankering for just such a creature and was looking forward to ordering them as soon as possible. Jo Ann even told us that she knew of a good place that did fried plantains and that if we wanted to we could go eat there on Saturday. Sounded like a plan to me.

The thing about the chips that continued to amaze me, though, were their price. Five cents American. I just marveled at it. Sure, it’s not like we were getting a Big Grab, or anything, but these bags represented the size you usually find with a child’s lunch. Not a bad size for a quick snack. And you couldn’t beat 5 cents. Jo Ann asked how much one would cost in America.

“Oh, fifty cents, easy,” I said.

They were appalled.

Unlike Guatemala, where the currency is Quetzales, El Salvador now runs on the American dollar. However, as you can see with the example of the chips, the dollar goes a lot further in El Salvador than it does back home.

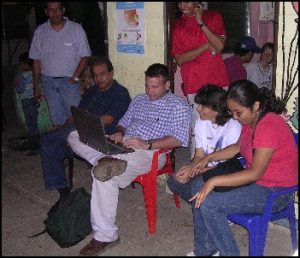

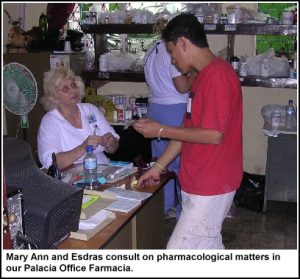

Thursday afternoon we were joined in the pharmacy by two new translators, whose names were Rosio and Claudia. They were very sweet young ladies who were very good at their job of translating. Some might say too good. So far Jo Ann had pretty much stuck to our standard prescription instructions of telling each patient how often to take their medicine and for how many days and circling this frequency on our graphic-based instruction slips, or, if the instructions were more complicated, she would write them out, but for the most part she kept it as simple as possible. Rosio and Claudia, however, felt it necessary to not only explain all instructions in graphic detail but to write them all down in graphic detail as well. This might not have even been an issue, except that we still had Dr. Grace with us and she continued whipping through patients at an astounding rate. Soon the pharmacy had a line of patients fifteen feet deep and it stayed that way. Mary Ann and I were filling prescriptions as fast as we could, but then these filled prescriptions had to get in an ever-lengthening line to have their instructions notated, which–as the “pharmacists” on hand–we also had to be present for to make sure they were done right. It was gumming up the works and was beginning to put me into another foul mood.

I tried to explain to them that this was not a productive or efficient way to run a pharmacy. Sure, it was very nice that they wanted each patient to have exact instructions on when and how often to take their meds, to the nearest hour, but this wasn’t rocket science and our former method of telling patients “Uno por dia” and “Dos diarias” worked just fine for telling patients to take pills once or twice a day. Now, granted, if a prescription was more complicated than taking a pill a specified number of times per day, we did then have a medical obligation to explain it and write out the instructions accordingly. However, for the vast majority of prescriptions we could just circle the little pictures on the instruction slips.

Rosio did not agree with this at all. I don’t know if she didn’t think the people were smart enough to follow the graphs or if she thought they would forget what we told them, but she did not like it that I wanted her to stop writing out all the instructions. I tried to explain that we’d been using the graphs and simple instructions quite successfully for not only this week, but a four clinics in Guatemala before this and had no known problems. Taking the amount of time we were with each med was slowing everything down to a crawl and causing the patients who had been waiting to be seen for most of the day to have to wait even longer before they could leave. All we needed to do, as I saw it, was fill the prescriptions, circle the correct pictures on the instruction slips, explain each slip in regards to each medicine to the patients and then put those slips into the individual med baggies or otherwise attach it to the med bottle itself so that they wouldn’t be confused with other meds.

Rosio didn’t like it, but she and Claudia agreed to do it my way. Of course, the first patient Rosio tried my method on was a kid in his late teens who gave us the blankest of looks when Rosio told him the instructions for his pills. He looked at her like she was speaking English, or something. She told him the instructions again, very simple instructions that he was to take one pill three times per day until they ran out, but again his expression spoke volumes about just how much he didn’t get it.

“Uh, maybe you’re right after all,” I said. After that we kind of met in a middle ground of our two methods, altering it on a case by case basis.

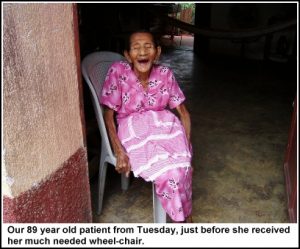

At the end of the day, one of the last patients to be seen was an elderly woman. She explained to Dr. Allen that though she had been waiting for much of the afternoon, there wasn’t actually anything wrong with her. She said she lived nearby and had several children and grandchildren living with her. Due to circumstances, the grandchildren were largely unable to work, so she was the primary bread-winner for the household in her job as a housecleaner. Her family was understandably very poor and had little money to spend on anything fun for the kids. She had been told that our clinic had been giving out toys and candy and she had walked here and signed up to be seen on the off chance that we had some toys and candy we could give to her to take home. Dr. Allen was very touched by her story and loaded her up with toys and candy and vitamins for her whole family.

Our clinics ended around 7 that evening and we were able to head on back to WOL headquarters for a much earlier supper than the night before. Some of the translators from our week would not be returning for our Friday half-clinic, so we had something of a tearful farewell with them Thursday night.

EL SALVADOR CLINIC DAY 3 STATS

Patients Seen: 218

Prescriptions Filled: 586

Salvations/Rededications: 67

DATELINE: Wednesday, March 30, 2005

Breakfast worked better this day. We got toast and jelly and it didn’t even take all that long.

Ash took my list of meds we’d run out of or were otherwise low on and headed to a local pharmacy with Jo Ann and Butch. The rest of us piled into Sylvana’s van and headed back to our pre-school clinic site.

We had nearly reached our clinic and were passing near the new neighborhood clinic site—the one with no staff and no medicine—and were a bit surprised to see a great deal of activity around it. The gates were open and there were many people standing around outside with decorations. In fact, the road past it had been blocked off due to all the new vehicles so we had to take a different route to our clinic. Later, Jo Ann explained to us that this day was the grand opening for the neighborhood clinic and there would be much celebrating going on there throughout the day.

“But they’re not really about to open, right?” I asked.

“No,” Jo Ann said. They still had no staff and no meds and no money for either, so the actual opening day was still months and/or years in the future.

“Huh.”

Despite that, the grand-opening celebration did continue throughout the day. We knew this because we could hear loud music coming from the direction of the other clinic which was broken up only by incredibly loud fireworks that sounded exactly like mortar shells going off. Tremendously loud. I thought for a moment they were indeed firing rounds into the air, because it was that loud. It made for a very trying day, because it seemed like every time I had to measure something into exact amounts in a delicate fashion, BOOOOM! and I’d nearly spill everything. Fortunately, there was not a lot of blood to be drawn in our clinic, or I could see horrible ramifications of the explosions. This went on throughout the morning and into the afternoon, making us all extremely nervous as we tried to go about our business in what sounded like a war zone. I began to suspect they were doing it on purpose to try and get back at us for inadvertently showing them up at their own job. I mean, how dare we open up a free clinic and treat patients when there was a perfectly good pay-clinic, with balloons, food and fireworks, albeit utterly devoid of doctors and medicine, just down the road?

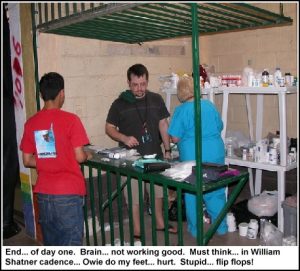

Meanwhile, we had far more patients to see than the day before. Apparently word had spread of what we were doing. Fortunately, Dr. Grace was still with us, so we passed out extra number tickets that morning so we could see more patients. This would turn out to be a decision with ramifications.